February/March 2018

As Maine goes, so goes the nation. It sounds so encouraging. But is that true with women’s rights? Prepare for some surprising facts across the decades…

By Olivia Gunn Kostishevskaya

In front of the departure gate of the Portland Jetport on a crisp November morning, 19 Maine women get out of cars and taxis and assemble in the airport lobby.

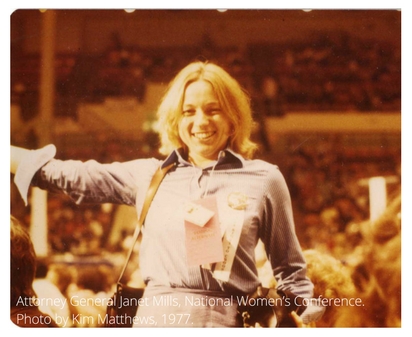

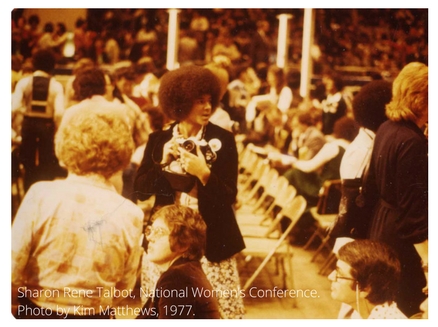

Imagine: Here is Merle Nelson greeting Sharon Rene Talbot and Linda S. Dyer. Next comes Vivian Massey, JoAnn Fritsche, Kim Matthews, Anne Hazelwood-Brady, Nan Stone, Cynthia Murray-Beliveau, Lois Reckitt, Constance Depew, Kate McQueen, Paulette Dodge, Claire Hussey, Janet Mills, and Pat Ryan. (If you or one of your relatives were in attendance, let us know at editor@portlandmonthly.com.)

Should one of them need to use the airport “powder room” before takeoff, she’ll have to pay a nickel to enter, though access to the men’s restroom is free of charge–just one of many frank injustices that have turned a slow burn into something very hot.

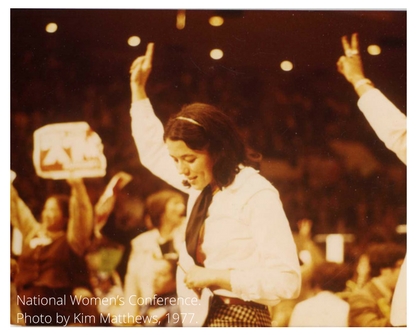

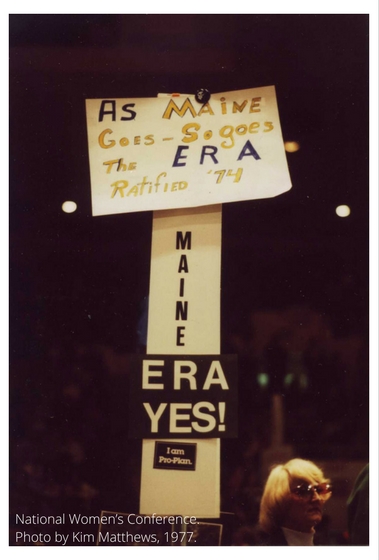

The destination? Come fly with them as they lift into the flight levels and soar over Boston and New York and into a brighter future. These Downeast ladies feel a rush of excitement, because they’re heading to Houston, Texas, as Maine’s delegates to the first and only U.S. government-funded conference of its kind. The 1977 National Women’s Conference, attended by 20,000 leaders from across the country, will be a unifying assembly to address neglected issues from equality, to education, to reproductive rights. Though it sounds like the start of a kick-ass new Netflix series, this legendary trip will be an igniting spark. It lights up an organization called the Maine Women’s Lobby over 2,000 miles away. As you read this, the Lobby is celebrating its 40th year in search of justice.

Up in the Air

With ABBA’s “Dancing Queen” playing in her head, State Representative Lois Reckitt, who will later become Vice President Executive of the National Organization for Women, looked out her Boeing 727 window to see the clouds and cities below as she rushed south. “It was very energizing and exciting,” she says. “Every time the plane stopped” at connecting cities on the way to Houston, “more delegates got on,” from other states. “The plane felt full of us.” She ruefully remembers the flight attendants–“who I fear may still have been referred to as stewardesses at the time”–were supportive of the mission.

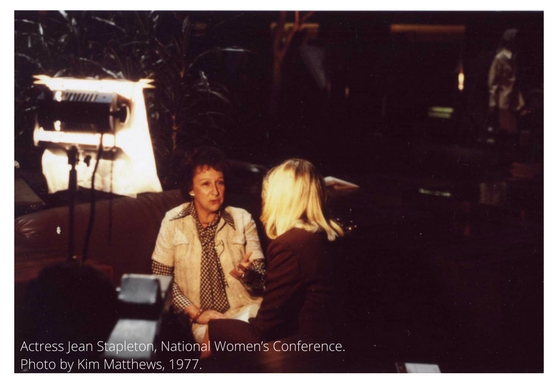

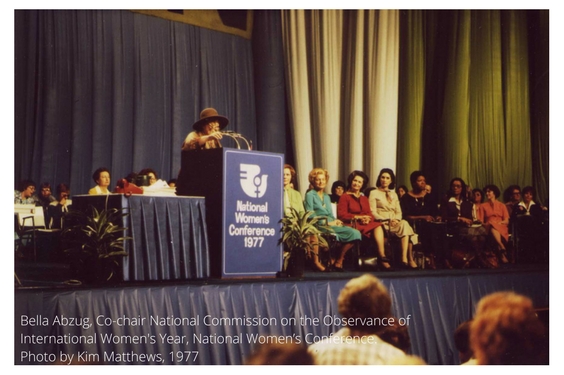

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. Once in Houston, the group arrived at the hotel to find a conference for overwhelmingly male building contractors refusing to leave. “It was really a mess trying to get into the hotel. I remember Bella Abzug (chair of the National Commission on the Observance of International Women’s Year and head of the conference) came tearing into the lobby, practically mowing me down.” These women meant business.

The Task at Hand

Specifically, issues on the table for the 19 Mainers covered the Equal Rights Amendment, shelters for domestic violence survivors, sexual assault crisis services, equal pay, and pregnancy discrimination. Reckitt says there was one major contention: whether or not to openly support lesbian rights. “There was some concern it would hinder our organizing attempts,” she says. “At the conference, there was an effort by some to identify everybody who wasn’t ‘out.’ There was a code that if you wore a yellow smile button, you were either lesbian or supportive of the issues.” Reckitt, who had just recently come out, remembers stepping into an elevator and being handed a button. “It felt like a safe place. The ‘antis’ were all the way across town at some rally after not being able to get enough delegates to make any difference at all,” she says with a laugh. The turning point on the gay rights issue was when Betty Friedan, co-founder and president of the National Organization of Women, who was known to take an anti-LGBT stance, stood up and spoke in support.

Return Flight

The world had changed during the conference. Now it was time to bring change back to Maine.

The delegates landed back home with a “gentle, optimistic energy fueled by unity of purpose,” says Maine Attorney General Mills. After the trip to Houston, the Attorney General’s Office partnered with the ACLU to hold the first Maine Women’s Conference at Colby College. “Our original meetings were small gatherings in someone’s apartment or someone’s office, conniving in rooms to raise money, to spread the word, and to develop some presence, status, and respect in the halls of the State House.”

During the 1978 Maine Legislative Session, the group worked to fund battered women’s shelters. “They had testified, written letters, found sponsors, agreed on a budget–all of it,” says Maine Women’s Lobby Executive Director, Eliza Townsend (above right). “But, when the session concluded, there was no money appropriated for the shelters. The group was told that in the middle of the night when the decisions were reached, there wasn’t anyone present representing them.” After the defeat of the Battered Women’s Projects (BWP) in 1978, the women “learned, regrouped, and vowed never again” would they be unrepresented during a legislative vote.

At the time, it wasn’t just the halls of Augusta lacking female representation. At the Maine Women’s Lobby Celebration in 2014, Mills described the dichotomy of the time: movements like women’s rights continued to gain intensity, but women continued to be underrepresented in the workplace. In 1978, 92 students graduated the University of Maine School of Law–only 21 of them women (Last year, women made up just under half of the class.) “There were even fewer role models for women who wished to work construction, in the trades, or in law enforcement,” says Mills.

A Different World

Anyone who considers this nostalgia isn’t keeping her eyes open. Yes, this was a different time, though recent headlines do have us wondering just how far we’ve come. Three years after this flight, the Portland International Jetport still maintained pay toilets in the women’s restroom, but not the men’s. The reasoning? Women’s toilets required more cleaning. Other states across the country had already banned the practice in the mid-1970s, following efforts by women’s groups and the Committee to End Pay Toilets in America. In a 1992 Portland Press Herald article, former Portland mayor and city councilor Linda Abromson recognized the city’s removal of those toilets as her first legislative victory. Across town, The Portland Country Club hosted a men-only tee time that excluded female members. Finally, in 1991, the club amended those by-laws to “afford women the same rights of membership as men, including the same access to tee times.” “The club leaders recognized the rules and by-laws were archaic,” says member Kathy Drake. While women’s pay toilets and golf course restrictions gall today, they pale in comparison to the darker issues the MWL faced in state legislation. It wasn’t until 1985 that the Spousal Exemption, which did not recognize marital rape as a crime, was removed from Maine’s sexual assault laws. In addition, language was added that no longer made rape a “lesser crime” if it occurred on a date.

The Road Ahead

In a state that ranked ninth-highest nationally in homicides against women by men in a 2013 Violence Policy Center study, change hasn’t gotten any easier. Domestic violence continuously makes up 50 percent of these homicides each year. “As you can see from the #MeToo movement, we still have a lot of work to do on attitudes and social structures,” says Townsend. “It’s the complex nature of the issues and the tendency in the media to reduce the issues to sex and body parts–or even something as simple as the five-cent bathroom fee–though it is appalling.” Much of the lobby’s work centers on economic stability and violence against women. “Money is the overarching issue above anything else,” says Townsend. “Whether you have money, what you have to do to get money, and whether or not you stay in a relationship that’s not working–everything is shaped by money.”

There has been positive change. Townsend notes the expansion of Maine’s Family Medical Leave law to include domestic partners in 2007 as a highlight. In 2015, L.D. 921 was passed to provide more extensive protections for victims and survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking in the workplace. Penalties increased for employers who fire employees needing to take time off to attend court dates, doctor appointments, and other related burdens. But as Maine continues to evolve, new challenges emerge. According to the Immigrant Resource Center of Maine, there are now approximately 7,500 East African immigrants living in Androscoggin County, and around 5,000 living in Cumberland County. In 2014, Maine saw 158 cases of violence against East African women, of which 60 percent were domestic violence and 30 percent were cases of sexual assault. Mufalo Chitam, Executive Director of the Maine Immigrant Rights Coalition and former MWL board member, believes inclusivity of immigrant women is key to progress, along with efforts to foster trust between communities and institutions such as law enforcement. “We need to harness the full potential of immigrants with skills and education to thrive, exploring ways to leverage the new untapped talent in our state.”

It was determination, passion, and devotion that 19 Maine women tapped into 40 years ago on an historical journey to Houston, returning home inspired and ready to work. It was the same energy that brought over 10,000 women and men to the streets of Portland in January 2017 for the Women’s March. Looking back on the 1977 rally, Attorney General Mills says a Margaret Mead quote comes to mind: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” She ascribes it to “the mischievous band of determined women, ages 18 to 64, who listened to rousing speeches in Houston, and the many others who dug into issues at the 1978 statewide conference…” As for Reckitt’s proudest moment of the Maine Women’s Lobby? “We’ve lasted 40 freaking years. That’s really kind of amazing when you think about.”

Photos below by Kim Matthews.

0 Comments