February/March 2014 | view this story as a .pdf

“Obama ‘loves’ black newspapers,” praised the Florida Courier as the president celebrated the 185th anniversary of Mainer John B. Russwurm’s founding of Freedom’s Journal during a White House fête to cap off Black Press Week. If only they’d held the party closer to home, in Portland, where Russwurm’s home still stands.

By Gwen Thompson

The cozy double front parlors–complete with working fireplaces, hardwood floors, six-over-six windows, Federal woodwork, and Greek Revival moldings–on the first floor of the two-story, white clapboard house opposite Cheverus High School on Ocean Avenue seem perfectly suited to sedate grown-up activities like crosswords and cocktails; while the slant-ceilinged, loft-like nooks and crannies connecting to a walk-in attic at the back of the upstairs strike one immediately as an ideal setting for kids to engage in more strenuous pursuits such as hide-and-seek. This duality of purpose no doubt came in handy between 1812 and 1838, when the John Brown Russwurm House–built c. 1810 and now a Greater Portland Landmark listed on the National Register–may have been home to as many as 14 children of parentage as oddly mixed and unlikely as anything you’d encounter on a modern TV sitcom.

The cozy double front parlors–complete with working fireplaces, hardwood floors, six-over-six windows, Federal woodwork, and Greek Revival moldings–on the first floor of the two-story, white clapboard house opposite Cheverus High School on Ocean Avenue seem perfectly suited to sedate grown-up activities like crosswords and cocktails; while the slant-ceilinged, loft-like nooks and crannies connecting to a walk-in attic at the back of the upstairs strike one immediately as an ideal setting for kids to engage in more strenuous pursuits such as hide-and-seek. This duality of purpose no doubt came in handy between 1812 and 1838, when the John Brown Russwurm House–built c. 1810 and now a Greater Portland Landmark listed on the National Register–may have been home to as many as 14 children of parentage as oddly mixed and unlikely as anything you’d encounter on a modern TV sitcom.

Back in 1799, when the house’s namesake was born out of wedlock in Port Antonio, Jamaica, to a white planter from Virginia and his Creole mistress, miscegenation was by no means uncommon. What was unusual was that John Russwurm Sr.–perhaps inspired by his own education in England–took such an interest in his illegitimate son’s schooling that he sent him to Quebec at age eight to get the education he couldn’t have obtained in the land of his birth. Even more remarkable is that after Russwurm Sr. resettled in Maine (then part of Massachusetts) on a 75-acre saltwater farm in Back Cove in 1812, his new bride, Susanna Blanchard of Yarmouth–a widow half his age who already had three children of her own–insisted that her husband’s mulatto son join them in Portland as a full member of their new family.

Indeed, her devotion to her black stepson ran so deep that her own children sometimes teased her about preferring him to her white children. This bond became even more crucial for the boy when, after having one child with Susanna and introducing John Jr. to “the best society in Portland, where he was honored and respected” (Proceedings of the Maine Genealogical Society), John Russwurm Sr. died in 1815.

Even after Susanna married for the third time in 1817 and had seven more children with William Hawes–a widower who owned a sawmill in North Yarmouth and brought to the union two children from his first marriage, making a grand total of 14 children from six different parents all living together under one roof in Portland–her dedication to her second husband’s son continued unabated. Russwurm managed to attend Hebron Academy despite the financial hardships implied by a second mortgage taken on the Portland farm in 1814, and graduated in 1819.

After four years spent tutoring black children in Boston, Russwurm entered Bowdoin College in 1824 as a 25-year-old junior “with aid from others augmented by his own exertions” (Nehemiah Cleaveland’s History of Bowdoin College, 1882).

In his Personal Recollections of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Horatio Bridge (class of 1825 and later Paymaster General of the U. S. Navy) records that at Bowdoin, Russwurm proved to be “a diligent student, but of no marked ability. He lived at a carpenter’s house, just beyond the village limits.” It is unclear whether this quasi-exile was entirely self-imposed or externally inflicted by college regulations, but if Russwurm lived off campus because he felt uncomfortable dwelling in the thick of Bowdoin’s social scene, he was not alone in doing so. A monograph on “Antislavery Materials” at Bowdoin College edited by Angela M. Leonard notes that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (class of 1825) felt so out of place as a 14-year-old freshman that he resided much of the time at home in Portland. At any rate, Russwurm’s color did not keep Bridge and Hawthorne from hiking out to call upon him several times at his off-campus digs–although Bridge does report that Russwurm’s “sensitiveness on account of his color prevented him from returning the calls”–nor did it deter Hawthorne from inviting him to join Bowdoin’s Athenaean Society, the more progressive and Democratic of the college’s two rival literary organizations. This invitation Russwurm accepted “with alacrity,” thereby becoming the first black man in America to join a college fraternity.

It seems likely that Russwurm’s years at Bowdoin were instrumental in the development of his interest in the abolitionist and colonization movements’ answers to the slavery question then dividing the nation. One of his professors, William Smyth, was an ardent abolitionist, while another, Thomas Cogswell Upham, supported colonization. Moreover, legend has it that Upham’s house–now the John Brown Russwurm Center for Africana Studies at Bowdoin–was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Russwurm’s commencement address–which received coverage in Portland and Boston newspapers–focused on the successful Haitian slave revolt of 1804, and before he graduated in 1826 as only the third black man in America to be awarded a college degree, Russwurm had been planning to study medicine in Boston prior to emigrating to Haiti.

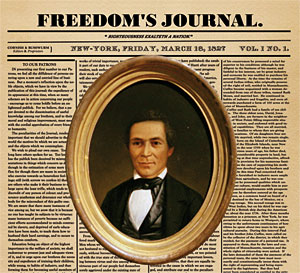

However, at some point his plans changed, and by 1827 he was well-established in New York City as co-editor, with the militant Presbyterian minister Samuel E. Cornish, of the abolitionist newspaper Freedom’s Journal, the first newspaper in America owned and published by African-Americans. The editorial of the first issue boldly proclaimed: “We wish to plead our own case. Too long have others spoken for us. Too long has the public been deceived by misrepresentations in things which concern us dearly.” The weekly publication of black news, success stories, literature, and letters filled a long-standing void in the struggle for black self-determination, and the paper was distributed in New York, New Jersey, Maine, Massachusetts, and even in such slavery strongholds as Maryland and Virginia, and as far afield as Canada, Haiti, and England, with an estimated circulation of 1,000 (John Brown Russwurm by Mary Sagarin, 1970). But a little over a year after Freedom’s Journal’s inception, Russwurm had grown so discouraged by the lack of progress towards the abolition of slavery in America–despite ever more violent agitation for it–that he reversed his position completely and declared that emigration to Africa offered blacks the sole remaining hope of achieving dignity and independence.

This about-face so angered steadfast abolitionists that Cornish left the paper, Russwurm’s former supporters burned him in effigy in the streets as a traitor to their cause, and Russwurm himself resigned as editor in 1828.

Putting his money where his mouth was, Russwurm sailed for Liberia in 1829 under the auspices of the American Colonization Society, an organization ostensibly founded to help former slaves attain a better quality of life in Africa than was available to them in America, although its opponents suspected an ulterior motive of eventually ejecting all freedmen from the country they had broken their backs to build. As superintendent of schools, colonial secretary, and vice-agent in Monrovia, Russwurm proceeded to run himself ragged establishing a school system for colonists and natives, learning and teaching new agricultural methods to the other colonists, negotiating with warring native tribes who regarded American blacks as “white” interlopers, and publishing the Liberia Herald. But whenever conflict arose, Russwurm found himself progressively demoted for his pains by the white Americans who funded the Colonization Society and could not, even at an ocean’s distance, refrain from regarding their adult beneficiaries as so many motherless children in sore need of discipline (John Russwurm by Janice Borzendowski, 1989).

But even under adverse circumstances in Africa, Russwurm continued to reap the benefits of his Bowdoin education. He became good friends with Dr. James Hall, an 1822 graduate of Bowdoin’s medical school who was working for the Maryland Colonization Society at their outpost southeast of Monrovia at Cape Palmas. When Hall resigned as Governor of the Maryland Colony in 1836 due to exhaustion, he recommended Russwurm to the Maryland Society as his successor. The Old Boy Network held strong, and Russwurm got the top job, becoming the first black high official appointed by the all-white organization. When Russwurm’s Bowdoin friend Horatio Bridge arrived at Cape Palmas in 1843 aboard a U.S. Navy warship hunting for slavers–proving once again what a small place the world is– he recorded with pleasure that the Governor of Cape Palmas “received, with dignity and ease, the Commodore and officers of our squadron, myself all the more cordially because we had been college associates and fellow-Athenaeans.”

The one thing that had sustained Russwurm through every disappointment and disillusionment was his abiding faith in the power of education to improve man’s lot in life. Thus it is no surprise that in 1849 he followed in his father’s footsteps by returning briefly to America to pay one last visit to his beloved white family and enroll his own two sons at Yarmouth Academy, which they attended while living with Russwurm’s ever-loyal stepmother. (In 1833, Russwurm had married Sarah E. McGill, the daughter of his predecessor as superintendent of schools in Liberia.)

While in Maine, Russwurm met for the first time another Bowdoin alumnus, U. S. Senator William Pitt Fessenden (class of 1823), who was so impressed with his abilities that he endeavored to persuade him to remain in America and dedicate his considerable talents to the anti-slavery cause in the States. Russwurm’s allegiance, however, could not be swayed from the new homeland to which he had dedicated so much of his life. He returned to Cape Palmas and continued to serve as governor until his death in 1851.

In 1997, 238 Ocean Avenue in Portland was listed for sale by Town & Shore Realty for $198,500, and it was scheduled to be the featured House of the Month in our Summerguide issue. That was before writer and Bowdoin graduate Gwen Thompson dug in and discovered this fascinating history. Thompson’s novella Men Beware Women was published in 2013 after winning the 2012 Miami University Press novella contest. Visit gwenthompson.us.

0 Comments