November 2018 | view this story as a .pdf

1: Feeling Geel

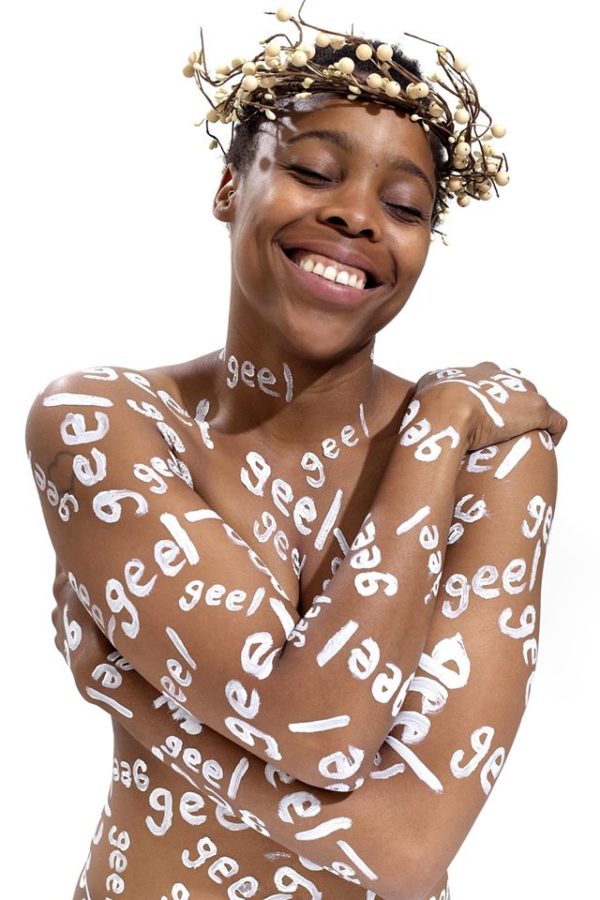

Artist René Goddess Johnson is soaring, and there’s no bringing her down.

By Diane Hudson

Something draws people to René Goddess Johnson. The South Africa-born actor, director, and choreographer has always snagged attention, at first by accident. “It started when I was a kid,” Johnson says. “Strangers would come up to me, sit next to me, and start a conversation. By the time I was 12, people would come up and tell me things out of the blue, like ‘my father just died.’”

Today, at 34, it’s a quality she prizes—“turning it into something. For 27 years, I’ve been fumbling and creating and somehow have become a director.” She smiles. “Producer. Performance artist. Educator. Dancer, choreographer, playwright, theater founder.” She almost twinkles. “Embodied equity consultant.

“My goal is to get more people to be embodied equity players. Growing up, we lose the ability to play. We need to bring ourselves back to the time as children when we were using our entire body and not worrying about looking stupid.”

She should know, having worked as a nanny for 17 years with no fewer than 33 babies.

Which brings us to her popular interactive one-woman show, geel. First performed at Celebration Barn Theater, geel has knocked out audiences at Congress Square Park, Colby and Bowdoin Colleges, and Bright Star World Dance. “I invite and give permission for the audience to actively participate throughout the show,” which includes powerful dance and song in multiple languages, including English and Afrikaans. This “brutally honest” production covers themes ranging from Johnson’s severe physical and emotional abuse and trauma to self-harm habits. “[I love] watching people believe they are going to be scared and then listening to them talk about how much fun they had.”

One standout memory is of a Portland woman in her late sixties. “I watched her listening. I knew she wanted to say something, so I asked her, ‘What’s on your mind?’ ‘I listened to that young man in the audience talk about skateboarding as a way to take care of himself. It never occurred to me I could do something I like for self-care.’ This is poignant,” Johnson says. “You don’t come to this show to find out about me. You come here to find out about yourself.”

As we speak, Johnson, the founder and artistic director of the four-year-old award-winning Theater Ensemble of Color, is collaborating with Portland Ovations and Portland Museum of Art on the production of the Alliance Theatre adaptation of Ashley Bryan’s picture book, Beautiful Blackbird. Inspired by a Zambian folk tale, the play, full of music and movement, traces Blackbird’s courageous journey to share his truth that “color on the outside is not what’s on the inside,” and “it is important for us to understand how we can get along together in this beautiful forest. This beautiful bird is telling people it’s ok to appreciate blackness, you are you and I am me.”

For director Johnson, “I had this book as a young black woman, and it meant so much. Someone was talking about my skin and my culture and saying it was beautiful. I wasn’t hearing this from church or school. This production is not about sadness, grief or suffering. It is about happiness, black joy, love moments. People don’t hear this enough about blacks. They see mostly police statistics.”

2: Fever Pitch

Reading a newspaper in Maine? Reade Brower likely owns or prints it.

Interview by Colin W. Sargent

After running with the bulls in Spain with his sons this past summer, Reade Brower, 62, shook Maine by the horns when he snapped up The Ellsworth American and The Mount Desert Islander.

He’d already collected virtually every other newspaper in Maine, from the Press Herald and Maine Sunday Telegram to Waterville’s Morning Sentinel, the Kennebec Journal, the Lewiston Sun Journal, Biddeford Journal Tribune, The Times Record, Portland Phoenix, The Forecaster newspapers, Rockland’s The Free Press, Belfast’s The Republican Journal, and The Camden Herald. Those he doesn’t have ownership interest in he probably prints, from the Bangor Daily News to The Bollard.

Not for the first time, print readers wondered, who is this guy? We caught up with him just before he left for Spain. His choice of venue? “Lunch at Moody’s Diner in Waldoboro.”

Portland Monthly: What’s on your mind this second?

Reade Brower: Right now it’s clear the desk so I can pack [to go to the Running of the Bulls in Pamplona]. Sometimes I’m asked for my long-range plan. I barely have a five-minute plan.

Sounds Quixotic. But running with the bulls seems

to fit in with how quickly you can jump to make a deal.

A Moody’s waitress approaches.

“What would you like?”

I’ll have what he’s having.

No, you probably won’t. I’ll have

scrambled eggs with cheese and

sausage and some hot tea.

I order a hamburger. Smoke from Brower’s hot beverage curls up from the counter at Moody’s.

Tea. Unusual for a U.S. journalist. You think of Clark Gable characters in the movies, downing cups of java. Don’t you like coffee?

I love coffee. I love coffee so much I used to bring coffee to bed with me. But I made some rules for myself when I got Crohn’s Disease. So I have a coffee allotment. I have rules. I only have coffee on Father’s Day, Christmas, a floating holiday, and two personal days.

Are those your rules or your wife Martha’s rules?

My rules. I lost 40 pounds in my 40th year. I pledged I’d give up coffee, alcohol, and doughnuts until I crossed various thresholds. I earned alcohol back. For 7,952 days, I’ve had no doughnuts.

Ever have questions about competing publications being printed under the same roof? Can’t they look at each other’s proofs—industrial espionage.

I rolled my eyes while you were asking that, because somebody could just be assigned to walk with [the client] and keep [the client] always in sight.

An elegant, low-cost solution. ‘Typical’ Reade Brower?

Besides, it’s already printed, so how could it be espionage?

After you started The Free Press, some might say you went dormant for 27 years compared to your feverish recent acquisitions. Who were you then—not acquiring other businesses for decades—and who are you now, where you’re expanding dramatically? In the movie of your life, there must have been a single, inciting incident.

I didn’t exactly go dormant. In the 1980s, I had many jobs. I did the Sunshine Guides. Eddie [Hemmingsen, who envisioned and ran the Sunshine Guides in the 1970s] had a heart attack, and I took over. [Brower owns the Sunshine Guides to this day, retitled as the travelMAINE guides]. I started The Free Press in 1985. Worked like a dog until 1989. When I had two infant sons under two, I sold it to a couple of really accomplished people. Eighteen months later, I bought it back.

“The arrangement was for them to pay Reade 25 percent of the purchase price and then $20,000 a year for 10 years. The deal provided some breathing room. And it allowed him to put a down payment on a house in Camden where [he and his wife] still live today.”–Pine Tree Watch

You had to repossess it?

Yes. That was in 1991. Nine months later, The Free Press was back on its feet. I now had three children. I solved some distributions problems, and then came the paradigm change: I began focusing on distribution more.

I mailed to residential addresses all over the state of Maine. I started Target Marketing and the auto catalogs. At my peak I was doing 65 million auto catalogs all over the country until 2004, when autotrader.com bought both Target and the auto catalogs.

A terrific coup! You could have done anything you wanted and never worked again. What’s intriguing is, why didn’t you live a life of leisure? What did you do immediately afterward?

I went to Malawi to work with a friend in an orphanage and get my head where it needed to be. Just a few weeks. Then I came back to Maine. I was 48. I don’t like to sail. I’m a nine-hole golfer at best. I like to run, so I did some of that. I wanted to work, but I didn’t want to just walk back into The Free Press. I just didn’t want to ask for a job and take someone’s job.

You really love The Free Press, the people there. It’s coming to me. All of this, this giant swirl of presses and newspapers, is just an extravagant way of protecting the interests of your core publication, the Free Press!

That’s right. I began RFB [for Reade Francis Brower] print co-op. That brought together six presses, and I made a deal with our competition, the Courier Gazette. But yes, from 2004 to 2011, I had a pretty easy life for six or seven years. Present father, present husband.

The Courier Gazette was your competitor, right? Though you were printing it.

In 2010, the Courier Gazette had to shut down their press. All of a sudden, the lights went dark. I was watching a basketball game. It was a Friday night, March 11, my mum’s birthday. I knew that no one in the stands knew that their paper had gone dark, that it was lost to the community. I knew it because he owed money to me [a September 6, 2018 Columbia Journalism Review story, “The Man Behind the Unparalleled Consolidation of Local News,” reports the debt to Brower at $75,000, for printing services]. At 5 p.m. there was an email. Then the website went dark. They’d lost their paper of record. I got a call from the bank. They were responsible [for the Courier Gazette’s financing], but they didn’t want to be known as the bank that shut it down. They asked me to work it out…

What is the strangest 30 seconds professionally you’ve had in the last five years?

I’m not sure it’s the strangest, but I was driving.

What kind of car?

A Prius. I’ve had five in a row. We were trying to get the contract to print MaineToday Media (MTM). If they shuttered their presses like Bangor Daily News did, we wanted the business for our press, so my partner Chris Miles (CEO of Brower’s Alliance Press in Brunswick) had gone to Connecticut to meet the front-line guy for Donald Sussman, Ophir [Barone], and he’d finally gotten permission to talk to Ophir. Chris called me.

“Are you sitting down?”

“No, I’m driving. Did we get it?”

“No.”

He told me that Donald Sussman couldn’t really let us print the newspapers because there were union considerations with their printing work force. So [Sussman] had a different idea. We weren’t there five minutes before Ophir said, ‘Why don’t you buy MaineToday Media?’ I thought, “Oh, no. What have I done?”

What is it you do?

I find ways to keep presses sustainable. I don’t think of myself as artistic, but this is my paintbrush.

What would it take for you to wake up and say, “It’s over. I don’t want to own a slew of Maine and Vermont newspapers anymore. They’re noisy and stress-ridden.” What would you do?

I’d find a person who would care about them.

Your hands-off approach to offer your [more than 30] newspapers their editorial autonomy is singular, noble. But every once in a while, do you get a phone call: “I just need you to tie-break on this one. This is an exception. Just this time.”

Never happened. The only time they’ll call me is to give me a heads-up [if they think we might get] sued.

If you were forced to give someone a 15-minute tour of your business, where would you take him or her? If you were Guy Gannett, we probably wouldn’t be here at Moody’s Diner, even though he probably was a customer here. Where would you take me to say, “This is where I work”?

I remember I went to [MTM] late at night. They wouldn’t let me in at first.

It’s an urban legend that you’ve only visited the Press Herald once after you bought it. So where would you take me?

I’d take you to MTM press. It’s a big building, so I could ditch you in there and get away.

How are you different from Guy Gannett, and what do you have in common? You’re both Red Sox fans, for starters.

I’m not hands-on. I only have to make two people happy. Me and the bank.

You don’t live in a Hearst Castle or in a Cape Elizabeth waterfront mansion like Guy Gannett. I can tell from Google Maps. How do you measure your success?

I like creating sustainable business models. I live in the same house I’ve lived in for many years. For success, I guess I’d ask myself, “How many lives have you affected in a positive way?”

Live below the fold but accomplish things above the fold.

I like that.

How far back does that approach go for you personally? Complete this sentence: In Westborough High School, you were the kid who (fill in the blank).

Fell under the radar there, too.

Any sports, extracurricular activities at Westborough?

Nothing very interesting.

Everything’s interesting. Your school colors were

navy blue and cardinal.

The Rangers. No, I didn’t have extracurricular activities. I worked as a bookkeeper for my father, Brower Engineering. I swept floors where my mother worked, King’s Department Store.

Many of us suffer from illusions, but you don’t seem to. Your email address ends with “rfbads.com.” Is it hard work to stay down to earth?

[A smile.] ‘I sell ads’ is what I’m all about. Newspapers have always been a labor of love. I’ve never made money just publishing newspapers.

How does the next generation of your family react to all of these acquisitions? You know, the ‘stewardship’ thing. Does anyone in your next generation want to get into the business to guide us all toward the 22nd century?

No!

With the Seattle Times needing cash, did the Blethen family take a $200M hit by divesting themselves in a hurry of Blethen-Maine—the Portland Newspapers, etc.? If they borrowed $213M in 1998 and sold it to the Richard Connor group of investors for something less than half of that, and Donald Sussman bought 75 percent of Maine Today Media for $3.3M in March of 2012, investing $13M according to one estimate, somebody had to be devastated along the way.

Donald’s $13M investment, to my knowledge, is accurate. He updated the infrastructure. He turned over a publication that was very nearly breaking even. The only problem was the print problem, and he had the unions. He couldn’t just contract the printing to me because of the print unions. The severance package [Sussman would have had to offer the union printers] was too expensive.

To get the savings you were offering, he’d have to sell everything to you.

Yes.

But you had a plan.

I took over the assets and some bank debt, and then I sold the [171,000-square-foot] MaineToday press building in South Portland [in early 2016, to J. B. Brown & Co., with CBRE/The Boulos Co. as broker, for $4.9M, including a 21-acre campus] and took a [10-year] lease [with renewal options] back. That was the money we used to buy the new press! Owning a building is not my core competency. With the new press, we’re saving $800,000 per year. It makes a red number slightly black.

Since then, much of the MTM editorial staff has moved from its rented headquarters at One City Center in downtown Portland to share space with the rest of MTM at Gannett Drive in South Portland:

“Most employees have been moved there from One City Center in Portland – where the company was paying $40,000 a month for rent and $100,000 a year for parking. Alliance will relocate to the South Portland plant in February–the Brunswick building was sold–and additional presses are being installed to produce the Alliance work.”–Pine Tree Watch

How do you feel about Canadian paper, and what are the purchasing trends?

The real challenge is the tariffs on Canadian newsprint. I can’t speak for the West Coast, but I do know in the East Coast, all newspapers use Canadian newsprint. All the U.S. [newsprint providers] are at capacity. It’s such an unnecessary thing. Pacific Northern is owned by a venture capitalist, [so why not work for self-interest and] leave the industry in the wreckage if the tariffs are not rescinded.

How have the tariffs affected your presses and publications in Maine, and what adjustments will you make?

Newsprint is the second-biggest expense outside of labor. It’s already been a challenge.

Geography aside, where’s the center of your business?

It’s close to wherever my minority partner Chris Miles is. He’s been running presses since he was a teenager.

You grew up a Red Sox fan. When The New York Times interviewed you and implied you were the ‘last man standing’ in a desolate world that was running from print, you made sure you were pictured in a Red Sox cap. Were you thinking “Yankees Fans?”

I didn’t realize the interview was about me. I thought he was going to be talking about [trends in print and publishing consortiums, consolidation].

Even though you control an electronic media empire as well, you seem a champion of print.

Now more than ever. I’m still the same person. I bowl on Tuesday nights. I’ve lived in the same house in Camden since 1989. With authority comes responsibility.

You’re pragmatic but sentimental. Or else you and Martha would never have started The Free Press on your wedding anniversary.

I know that’s been published, but it isn’t true.

It’s fair to say you’re working things out on a larger scale, then. It figures into your going to Pamplona. You could have shared some adventure with your sons in Maine. But this time around you needed a bigger canvas. There’s some searching.

For our 25th anniversary, Martha and I walked the Camino de Santiago. I’ve checked into some Zen concepts, read some Bertrand Russell.

It’s occurred to me that you can’t possibly receive all your newspapers daily or weekly and display them on a coffee table. When execs from your newspapers visit you, do you catch them looking anxiously for their title on your coffee table?

Nobody ever sees my coffee table.

What else do you like to, um, Reade?

I got the Al Franken book, but it was hard to finish. I liked Girl With A Dragon Tattoo.

It must be rewarding to have your dad living nearby.

I wouldn’t call it rewarding. I’d call it full circle.

Now that sounds like Girl With A Dragon Tattoo. If this were the Millennium Magazine interview, I’d query about your name, Reade. Sounds like a family name. How far back does it go?’

It’s German, like Brower, my surname. I’m adopted.

How did you and your wife meet? It’s a romantic story

that you followed her to Maine.

It’s not accurate. I met Martha at a Christmas party in Watertown, Massachusetts. [After having graduated from UMass Amherst, with a degree in marketing] I’d been living with my dad in Martha’s Vineyard for six months, and my next-door neighbor Renee invited me. The party was on Saturday night, December 20, 1980. I’d been doing some repairs–some spackling with my dad. We stopped for dinner. He looked up. “I thought you were going to a party. Eat your pizza. Drink your beer. Go to the party.”

I put on a pink shirt, made an origami bird, walked to Renee’s, and put the bird on the Christmas tree when I came in. Martha asked Renee, who put the bird up there? She was a first-year art teacher at Waltham High. When Proposition 2.5 happened, the school lost three art teachers, including Martha. Martha got a job in Thomaston after seeing an ad for the position in the Boston Globe. She was chosen out of 75 applicants as an art teacher.

Just fact checking. We’re in the 1980s. That was

a pink shirt?

Martha later made an artwork of it, in pink gesso. It hangs in our hallway: December 20, 1980.

What were you driving when you came to Maine?

A red early 1970s Toyota Corolla with some rust.

You’re an eye collector, working on a scale few can imagine. You’ve mentioned Martha’s image of your trying to put the pieces of a giant puzzle together before. But nobody’s ever wondered to ask you what the picture on the puzzle is. Do you have any idea of what the puzzle will look like when you’re finished?

I have no idea what the puzzle looks like. It would spoil it for me to see it. That’s the last thing I’d want to see.

For a list of Brower’s newspapers and printing clients, visit http://bit.ly/BrowerPortlandMonthly.

3: Stitch in Time

June Ranco, a member of the Penobscot Nation, guides her family’s 68-year-old Indian Moccasin Shop in Wells into the future.

By Mihku Paul

The Indian Moccasin Shop is still run by original family member June Ranco, who says, “We haven’t changed one bit. I think that’s why people like us so much.” It’s a small wood-framed storefront attached to a house on Post Road. Daylilies and irises grow alongside the worn front steps flanked by picture windows filled with Native American wares and souvenir items. A parking lot to the right features a handmade sign with blue lettering that reads “Parking for Indian Shop ONLY. Police take notice.”

As soon as you step inside, you’re enveloped in a delightful slice of Maine history. Glass cases filled with jewelry, statues, and bits and bobs fill every available space. Countertop displays feature bead strands and pouches as well as toys for children. Most of the countertop space to the right is filled with moccasins of all shapes and sizes. Some are clearly handmade while others are from a well-known artisanal moccasin maker in Minnesota.

Can you tell me how the shop started?

“My father and mother were in Ogunquit. That was about 1949. They were down there two summers, and then they decided they wanted something more permanent, you know, so they discovered this place. I believe they came here in 1951. When they found it, it was just that one room. It was a fish store, and guys from Massachusetts owned it. So they bought that and added this [storefront] on. They added their apartment on the back.”

Has your family always owned the shop?

“Yes, my father started it. They called him Chief Tomekin. He wasn’t really a chief, but that’s what people called him. He was Penobscot.”

June hands me a postcard with a group portrait of four family members in pan-Indian pageantry dress from an early era. I’m reminded of my own grandfather, who traveled in a Wild West show back in those days with Bruce Poolaw, a Kiowa who lived on Indian Island and had a souvenir shop there.

“This is my father, Leslie Ranco. That’s my grandfather, Joseph, and here is my grandmother and my aunt, who was called Princess Goldenrod. My mom’s picture is right here over the door. Her English name was Valentine Ranco, but her Indian name was Little Deer. My father made all the moccasins back then.”

Today, a Pow wow is held—the annual Val Ranco Pow Wow—each year in honor of June’s mother, Valentine, named for the holiday. This is the 16th year of the event, which started in 2008, the year Val Ranco passed. She was ninety-six, the oldest living Penobscot at that time.

At a recent clambake on Hermit Island, I learned from the campground owner that Princess Goldenrod used to come there each summer to sell her wares. June verifies this practice of summering in tourist areas along the Maine coast to sell Native crafts, which was common for the tribes in Maine back then.

Where do you get your moccasins from now?

“Well, I get some from Canada, you know. This here is Norwegian elk, and the leather has skyrocketed. My last guy told me, he says, ‘I don’t think I’m gonna be able to do this anymore because the leather is so expensive.’ And then he passed away anyway, so. So now I don’t have anybody, and I only have maybe one pair of these left now.”

Did you acquire any skills growing up, for beading and basketry?

“I used to make baskets, you know, and bookmarks and things. And I have a collection of small baskets that were made by different people years ago. This is sweetgrass right here. You know you can refresh that…just soak it in some warm water for a little bit. Did I tell you how they braided their sweetgrass? They’d go ’round by Skowhegan and that area and pick sweetgrass all day. Then they’d bring it home, and all the women would have their own sweetgrass, you know. But it would be all loose, so what they did was, one night they’d go to this person’s house. Everybody would braid sweetgrass for her. They’d have a little lunch, and then they’d make it a night. They’d braid a hundred yards of sweetgrass that one night. Then the next week they’d go to somebody else’s house, and then she’d give them a lunch and they’d braid all her sweetgrass. Everybody helped. Everybody got their grass braided.”

Have you heard before of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act? I wondered what you might have thought about it.

“Well, I don’t know. It’s hard for me to say. Because I have people coming in here every day of the week, telling me that they have…whatever blood. Cherokee or whatever. I say, well, that’s nice. But when it comes down to that, like you say, with this arts thing… I don’t know, I think they should be registered or connected with a tribe somewhere.”

You always told me if something wasn’t local, you knew where it came from.

“Right, yes. I try to avoid that kind of stuff, you know, if I can. It’s so darn hard today. But most of my stuff, I try to get natural made stuff made by Natives, you know? If possible. And I get a lot of stuff made by Mohawks up in St. Regis. And now I’m getting these from Canada. From the tribe up there. Anyway, I try to get Native American stuff made by Native Americans. And some things we make right here. Like those dreamcatchers.”

Are you planning to retire at some point?

“When it comes to that time, which will probably be next year or the year after, something like that, I will be here still to help my daughter get acclimated and everything.”

It just wouldn’t be the same without you here to tell the stories.

“That’s what everybody tells me. They just thank me for talking to them. And I enjoy talking to ’em. Just like my dad. He’d stand right there, making his moccasins, and customers would come in here and talk, talk, talk. They’d talk for hours. And sometimes they don’t buy anything. He didn’t care. He says, ‘I just like to talk with them.’ So I guess I must take after him.”

At a spritely 88, June Ranco carries the stories that transcend across generations of Maine. It you’re willing to listen, she’s willing to tell them. “They love it,” June says, “and they’ll ask me questions, and I’ll answer their questions, you know. And sometimes they buy something, which is fine. But they keep coming back, you know? They keep coming back. So that’s good.”

4: Skill Set

Ben Severance has real Maine stories to tell.

By Olivia Gunn Kotsishevskaya

While artists of his ilk are leaving the state for New York, Los Angeles, Atlanta, even Austin—Ben Severance, 30, has chosen a long-term relationship with the Forest City, where he lives in a shared apartment on Howard Street on Munjoy Hill. It overlooks a tangled garden and firepit where you’re sure to find a crew of Portland’s gaffers, producers, photographers, writers, and cinematographers talking shop on a warm night.

Being handed his father’s vintage Pentax camera presented an outlet for Severance growing up in Wilmot Flat, New Hampshire. It would lead to travel and work for organizations including the United Nations, Swarovski, and Habitat for Humanity. “I didn’t want to be in New York. I don’t like it,” he says over a beer at Brian Boru, the watering hole across from his office on Center Street. “And I’m from small-town New England. You don’t really look at Boston and dream of it. Portland feels, in some ways, like a West Coast city. We’re close to the mountains, the coast. People here value the things I value.”

Severance pursued photojournalism at Western Kentucky, where he met some of those whose famous photos hung on the walls of his childhood bedroom, including Sam Abell and David Alan Harvey. But it wasn’t all quite what he’d imagined. Focused on what he calls “cause-based photography,” he admits he became a bit disillusioned at one point. “They say you shouldn’t meet your heroes. Some were egomaniacs. And presenters would come to the school and say, ‘I don’t know why you all are in this.’”

None of which kept Severance from getting noticed. “There was some validation years later, after I’d sort of given up photo. Friends pushed me to submit to Eddie Adams Photo Workshop,” a creative mecca that accepts around 100 participants. “At the end, Santiago Lyon, my mentor throughout and head of the Associated Press, said I could go anywhere in the world, some foreign city, and just start working. That made me feel like I could put photo to rest because at that point, I was already hooked on video.”

He launched Timber and Frame in 2012 and started working with a non-profit in Ohio before he snagged his first commercial gig for Country Crock. “That was an existential crisis–whether I was going to do that or not. But, we ended up doing it. That launched us into a world of New York ad agencies.”

Now in Portland, Severance leads a team of Maine freelancers—“as good as any out of New York or the West Coast. There’s a stigma that good creative in our field–video and commercial production–has to come out of New York, L.A. That’s absolute bullshit. With the internet, you can have amazing creative coming out of anywhere in America. I challenge anyone on that fact. I face [that misconception] when I interact with clients in L.A. and New York. ‘Why are you in Portland, Maine?’ Well, young people like myself don’t want to live in New York. I have so many friends in New York looking out windows dreaming of living here.”

Big-city mindsets aren’t the only challenges Severance is taking on. “When working with local organizations, we’re working really hard to bring diversity in all forms to our work when maybe clients aren’t calling for it or aren’t even aware that it’s something they should be considering. We’ll tell them that’s a problem. I’ve had clients say, ‘That represents the demographic of Maine,’ but I don’t think that’s an [acceptable] excuse, and it’s definitely not an excuse for traditional gender stereotypes. We want to show it’s not just white people here. When we filmed for the United Nations in Portland, people who’d come from all over—Somalia, Sudan, Iraq—they’d grown up in these communities such as East Bayside and have said things like ‘I’m a Mainer. Portland is diverse.’ Their experience is so different from what the outward appearance of Maine is.”

Those shallow conclusions from the outside is the fuel Severance is burning on. “We have a place of power. I can influence the actors, talent, scenarios that go into the commercials that people watch on TV that represent Maine. I can push for that imagery to undermine a lot of stereotypes. And we want to work with organizations that value the fact that when we’re filming and need someone working with a chainsaw, it should be a young woman. ‘Oh, we need someone on a mountain looking out longingly.’ Great. That person should be a man.”

On top of changing the composition, Severance has his ear to the ground for real Maine stories. “We were brought on to do a commercial for a hospital system that spanned the entire state. Every visual they wanted to shoot was on the coast—sea kayaking, sailing, lobster boats, lighthouses. I said, ‘Guys, this isn’t Maine.’ Mainers aren’t getting together in groups and sea kayaking around! Let’s get real. If you’re marketing to Mainers in interior Maine, then you probably want to show four-wheeling. But hikers on the coast hate four-wheelers. If you show sailing, Millinocket will groan. There’s this balance, right? How do you walk that line and show what the core of Maine is about and cross that divide? When we’re talking about diversity of race and gender, diversity of class is equally as important. The people of interior Maine don’t get represented. I’m from a small town—not in Maine—but New Hampshire. My dad was a carpenter. I get it. If you’re talking to Mainers, you’ve got to get into what those people value and it’s very different. Those are battles.”

While agencies already have their pick of filmmakers, writers, and artists in bigger cities, Severance wants the Portland brainpower to stay right here. “The only way young, homegrown talent can stay is if there is enough of an economy here to work as a freelancer. One way I combat the brain drain is by hiring a crew here and taking them down to New York. That way the money is going back to the merry men up here in Sherwood Forest, and we’re just stealing it from down there in New York. And that’s what gets me through those awful days in New York.”

As for the work, Severance is busy producing videos like “Fisherman,” a two-minute PSA telling the story of a third generation lobsterman for The Nature Conservancy. Last year, he was hired by the United Nations to film “Another Silent Night,” depicting the stories of refugees. Much of that was filmed right here in Portland. Other projects include videos for Friends of Acadia, Motorola, and the Blanchard River Watershed Partnership in Ohio, a PSA that won a 2014 EMMY.

It’s hard not to get behind this Robin Hood. Severance is in for the good fight and has a vision many in Maine are seeing clearly—one that extends beyond the screen.

5. Embedded in Maine

Abdi Nor Iftin has everyone talking.

By Olivia Gunn Kotsishevskaya

In Call Me American (Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), Abdi Nor Iftin, 33, chronicles his life in war-torn Somalia from his childhood to his immigration to the United States. It’s a harrowing reality that few U.S.-born citizens can fathom.

“Mogadishu had become a city of women and children, a city of graves. The streets were littered with bullet casings and unexploded bombs. Exhausted militiamen roamed the empty neighborhoods, roofs and doors gone, carrying the goods they looted going from house to house, leaving nothing behind. The great capital city of the nation had become the valley of death.” —Call Me American.

“It’s important that we share these stories with the entire world so they know,” says Iftin, who first began telling his story as a correspondent for the BBC and NPR in 2009 via secret cell phone recordings after meeting Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Paul Salopek in Mogadishu. Salopek was there covering the U.S.-backed Ethiopian occupation.

At the time, Iftin was 22, had witnessed more death as a child than most adults, had buried his infant sister, had lived on the streets, and was threatened with a gun to his head. Each day, for most of his life, presented a thin line between life or death. “Living with violence was the only thing I knew,” Iftin says. From avoiding the militant group al-Shabaab and navigating the sheer chaos around him, it seemed there was no escape. Well-known as “Abdi American” for his obsession with Western culture, he was watched closely by the group. Iftin learned English from Hollywood movies starring Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger screened in a neighbor’s home. It was an escape as much as an opportunity. “In the movies, there are good guys and bad guys. Where I lived, there were no good guys.” With a Madonna poster hanging in his bedroom and rap music playing, Iftin could tell his mother was at a loss. “She had never seen someone so obsessed with Western culture.”

On top of it all, Iftin was teaching English to others, drawing more attention to himself. “They [al-Shabaab] were trying to recruit me. I hid in an area al-Shabaab was not controlling at the time, and, luckily, I met Paul. He listened to me. I was so frustrated, and I unleashed all the frustration and anger I had. I told him, ‘Life here sucks. I can die anytime any moment.’”

Salopek brought the accounts back to the U.S., writing a piece for The Atlantic, “The War Is Bitter and Nasty.” It was the inciting incident in Iftin’s trek to the U.S.

With the help of the NPR team and the McDonnell family from Maine—who’d listened with rapt attention to Iftin’s story on the airwaves, Iftin escaped to Kenya, where he entered the lottery for a green card and was selected to immigrate to the States. Arriving in Boston, where Yarmouth’s Sharon McDonnell and her daughter Natalya were there to greet him, Iftin recalls seeing headlines on Michael Brown on the televisions at the airport. Having finally made it to Maine, Iftin spent his first night with the McDonnells in Yarmouth. “The next day [in Yarmouth] they took me around the neighborhood…it’s really, really less diverse. Basically, we went to the neighbors and we told them, ‘Please, don’t call 911, I am a local who just came. I am not a troublemaker, and I’m so excited to be here.’ So, that was my introduction to America, unfortunately.

“Maine did not look like the America I had imagined. In Yarmouth, people have horses, chickens—there are deer, turkeys. I thought, ‘Why does this look like the scary movies?’ Two years into Maine—once I got my car, a job, and I met some friends—I moved into Portland. I’m going to the ocean in the warm weather. In the winter, I had people show me how to do ice skating, and I got snowshoes—everything many Mainers do.”

Though he’d been sending ground reports and recounting his daily survival, Iftin says it was tough to invoke those dark childhood memories for the book written with Max Alexander. “It was difficult writing those things,” he says. “My mother is in Somalia, and my brother is a refugee in Kenya. It was difficult because I called my mother and asked her to describe what it was like in the civil war. I asked her about the survival, her strength, her nomadic skills she used, and we’d cry. She just wanted to forget it and focus on surviving. I could feel the nightmares. They felt like fresh memories. My mother felt the same way. But this was my memoir, and I wanted to write down these things so the whole world had to read about what it is like to grow up in civil war Somalia—how easy it was to bring down a government, how easy it was to get into a civil war, but how hard it is to get out of it.”

Today, Iftin works as a translator; as an author, he’s touring the country he’d dreamt of as a boy, though the widespread attention hasn’t only brought praise. Iftin’s Seattle appearance was cancelled this fall following controversy within Maine’s Somali community. According to the Press Herald, former roommates Yusuf Yusuf, Mohamed Awil, and Abdullahi Ali dispute what Iftin wrote about them in Chapter 16 of the memoir, which describes his life in Portland, and many are displeased by the way the Somali community as a whole is portrayed:

“My roommates had all been in Maine over ten years, making me the new guy in town. But I was surprised how little American culture they had absorbed…No one except me had a passion for America. Abdul was the only one who had even bothered learning English, which he needed for his work. In their jobs stocking shelves at Walmart and Shaw’s, Yussuf and Awil didn’t really need to speak English.” —Call Me American

In an email to Portland Monthly Ali writes, “The part of the book about Maine is mostly fabricated and plays to the general negative stereotypes to refugees/immigrants, Muslims, or people of color (lazy, uneducated, unwilling to integrate, hates America, care [for] their home countries more than the U.S.A. and not interested in becoming a part of the American society). These are the talking points of the far-right, anti-immigrant fanatics. What is more disappointing is that the examples used to justify these are made up or completely false.”

Ali was unable to discuss a lawsuit they are working on but sent a long list of disputed content. “We are not writing this to shame Abdi,” he writes, “but to point out misconceptions created by this falsified ‘memoir.’ As we have already indicated to him, we welcome a sit down with him, so that we may set the record straight and hopefully show him that he did not have to be creative with the truth or insult his origin[s] to sell a book.”

“The roommate [Ali] feels like I exposed some untold stories that would stay within us,” Iftin says. “But I decided to change his name because he does not want it in the book. My publisher is working on that.” Paul Boagaards, head of publicity for Penguin Random House, told the Press Herald that “a handful of changes, including names and text” would be changed in the electronic version and future prints.

6: River Queen

Kayaking helps Kimberlee Bennett ply new frontiers.

By Olivia Gunn Kotsishevskaya

The water, glass-like, reflecting fall’s beauty, shatters as the tip of Westbrook resident Kimberlee Bennett’s Old Town Loon kayak glides from the shore. We’re on Lower Range Pond in Poland, which, other than two fishermen in a small row boat, we have to ourselves. Gladys, Bennett’s canine travel companion, pouts over the edge of the kayak, disappointed in our lack of enthusiasm for a swim. With no solid plans or schedule dictating our route, we follow Maine Kayak Girl into deeper water.

“The first time I kayaked alone after I lost my mom was on the Penobscot,” Bennett, 43, says as we paddle past an island screeching with bald eagles. “It was something we’d always done together. I didn’t know if it would mean the same to me without her.” Bennett’s mother died in 2009, but her love for Maine’s outdoors still speaks to Bennett, whose blog, Recreational Kayaking in Maine, has gained a monumental following among adventurers looking for straight-forward info on the state’s waterways.

“I really started the blog as a way to keep track of my own trips,” says Bennett, an assistant principal at South Portland High School who, at six-foot six, says she loves being recognized for something other than her height. “I grew up in Lincoln, a small town, and I played basketball, so I was always known for being tall. After starting the blog, I remember being out [kayaking] alone and joining some other kayakers under a bridge. One of the women started talking about this blog she’d been following, and I just kind of nodded. Then she started looking at me and said, ‘Wait—are you…?’”

After her blog took off, Bennett was asked by friend and former registered Maine guide Sandy Moore to co-write and photograph for a book for kayakers, canoers, and SUPers. Paddling Southern Maine (Mountaineers Books, 2017) contains 54 adventures from lakes to coves and tidal rivers.

Though she’s spent time as an interstate toll collector while working three other jobs, Bennett now loves working to get kids at South Portland High accustomed to the waterways that make up their home state. “We have native Mainers and so many kids who are new to Maine—from other states, other countries—who haven’t yet experienced the beauty” of kayaking through time and silence. “Navigating is something they deserve to have. We’re hoping to plan a trip next spring. It helps build that confidence in kids to know they have the strength and ability to guide themselves and keep themselves afloat. It’s empowering for both young men and young women.”

Heading back to shore, our conversation slowly dissolves into the sound of our paddles in the water. I ask Bennett what’s on her mind when she loses herself in moments like these.

“Honestly, this is the one place I don’t have to think about too much.”

7: Babe on Beat

She’s drummed with the legends of rock. Now Ginger Cote is front and center as she transforms the former Griffin Club in South Portland.

By Sarah Moore

As contractors break ground on Big Babe’s tavern this month, owner and acclaimed musician Ginger Cote prepares to switch drum kits for draft lists. On the former site of The Griffin Club, she plans to establish a neighborhood music venue—her blueprint for the place an amalgam of the hundreds of clubs and concerts halls she’s played over her four-decade long career as a session, rock, and country drummer.

Born in Limestone, Aroostook County, Cote’s first brush with fate occurred while playing with a childhood friend and son of local drummer George Derrah in the family basement, complete with pinball table and two old Ludwig Sparkle drum sets. “I was pulled to them like a magnet. I picked up some sticks aged six, sat behind the Blue Sparkle, and without a clue what I was doing, began to play a beat. That was it–I was bitten by the drumming bug. George Derrah offered to sell my family the set. We didn’t have any money, so my parents bought it for me piece-by-piece. They must’ve been real gluttons for punishment.” From then on, Cote’s every spare moment would be spent in her bedroom, headphones glued to her ears and tuned into FM radio. Every song that came on, Cote would hit along until she found the beat. “This was the 1970s, so I was playing disco and Led Zeppelin.” Cote’s mother, an amateur singer, would be downstairs with Carole King and Clapton’s Slowhand on the hifi. Her father’s affinity for Merle Haggard and old-time country rounded out her musical palette.

The sight of a diminutive 11-year-old Cote wielding drumsticks on stage at a local club was a regular occurrence in Limestone in 1974, then a thriving nightlife scene fueled with crowds from nearby Loring Air Force base. “I’d play at the base and bars and clubs around town as a school kid, my mom standing at the back as my chaperone. Some weeks I’d play three to four shows on a school night. I’d be half-asleep in class the next day.”

After a year spent gigging in Montreal with the band Shadowfax post-graduation, Cote moved to Portland in 1986 with dreams of a career in music and only $50 in her pocket. “I slept in Deering Oaks for the first three nights before I got a spot at the YWCA. It was a very different town back then.” A job making sandwiches at Amato’s and a spot playing drums for The Brood at Geno’s (then on Free Street), Raoul’s, Free Street Taverna, and The Rat in Boston helped Cote establish herself as a force of the local music scene. “I was hanging out with Bebe Buell and The Gargoyles and Darien Brahms, playing music and drinking around town. It was a wild scene back then.” Cote’s big break came when Brahms introduced her to Cidny Bullens, the Maine talent famous for singing backup for the likes of Elton John and Rod Stewart.

Through raw talent and years of dedication, by 1999 Cote was living in Nashville and working as an A-session drummer, sharing stages and tequilas with Bonnie Raitt and Lucinda Williams. “My most memorable rock and roll moment? When Bonnie Raitt poured me a shot and helped carry my drum kit on stage.” She performed five shows in California with Emmylou Harris. She met Ryan Adams and spent days in the legendary local recording studios, “back before Nashville became the Walmart of music cities.”

Cote’s rise to the big leagues of session drumming in Nashville was especially impressive given the instrument’s assertively male-dominated reputation. “You really slipped through the cracks to get in here,” said one bass player with a sneer. Perhaps Nashville’s macho atmosphere drew her closer to those feminine forces of nature with whom she toured. “I spent one unforgettable night at the Exit Inn and Bluebird Cafe with Lucinda Williams—we probably had more than one or two drinks—as she unleashed a tirade against the white male rigidity of Nashville.”

Decades of hauling drumkits out of clubs at 2 a.m. has tempered Cote’s appetite for performing in recent years. A connoisseur of clubs, the idea of opening a music venue had been brewing for some time when she heard rumor that the former Griffin Club building at 60 Ocean Avenue was for sale. “I spent two weeks going there every night to really consider the atmosphere of the place. I got the feeling—this was the spot.” Tough research. While Cote hoped to restore the bones of the place, structural engineers advised her she’d be wasting her money. Instead she’ll rebuild the space, complete with soundproofing and two second-storey rooms for rent. The vision is for a down-to-earth tavern for music lovers and locals, with live sets Thursday through Sunday until 11:30 p.m. The legacy of The Griffin Club has left a rub of acrimony among certain diehards. “I’ve heard so much hurtful shit from people who are against it, but I know how much musical talent there is in Portland. SoPo is crying out for a venue, and I’ve gathered ideas from every club I’ve played in over the decades.” Can we hope to see her on stage some night? “I don’t know—we’ll see if I get a chance,” she says. Sounds like a promise to us.

8: Mystic

Vicki Monroe offers more than we bargained for.

By Sofia Voltin

The psychic is finishing up a session with a client while I wait in the lobby of the Kennebunk Inn. She knows what’s going to happen, but I don’t. The dining room is closed, so we have the space to ourselves, the overcast day providing just enough gray light through the windows. No candles, long robes, incense, or crystal balls are in sight. Vicki Monroe, 56, is wearing jeans and a lime shirt, her red curly hair pinned away from her face without much fuss. She greets me warmly, and we take our conversation to the empty dining room. Still, no candles. Rather, the interview and subsequent reading seems more like a lunch date. But in place of small talk about the weather, we circle topics of death, spirits, ghosts, the afterlife… You know, the typical pleasantries when meeting a psychic medium.

Monroe has been featured on radio and television shows, including Psychic Detective, using her gifts to help solve cold and active police investigations. During the high-profile Amy St. Laurent case, Portland police sourced Vicki for help, and she revealed information that head detective Joseph Loughlin told local media was “uncanny.”

“I was the last one of the day to go up for my baptism,” she says of her first spirit sighting. She was just four years old. “I walked up steps that were covered in a red rug, and when I hit the bottom step, it turned to stone. It became very cool in there. I could hear water dripping, and I’m thinking, ‘This is a ride!’ I’d just gone to Disneyland for the first time, so I’m thinking it’s like Pirates of the Caribbean, that kind of thing, right? I step up, and there’s this man, and all I can tell you is that he looked like Friar Tuck from Robin Hood. [He had] the bluest eyes I ever saw.” From that day on, Vicki would continue to see odd things every now and then.

Many years later, when Vicki lived in Germany, her sister Heather surprised her with a visit. “When I saw her, I said, ‘What’re you doing here?’ She said, ‘You’re going to get some news. It’s not the best, but I’ve got to tell you. Look at me now.’ I thought she looked amazing. I asked her, ‘Where’s Tom?’ Heather said, ‘He’s late. They’re working on him.’” That’s when Vicki realized her sister was dead. She received the call from her father later informing her of the car accident that’d killed both Heather and her husband, Tom. “After that, I was seeing things all the time. Not just random, little things. It was constant.”

As Vicki speaks, her gaze flicks away–only for a quick second–into the space beyond my left shoulder. I turn around, wondering if someone has entered the room. “For me, it comes like a wave. I’ll just hear them say this name, then this name. Sometimes, it resonates with somebody, and other times it doesn’t resonate until they get home. It just depends. I have to explain how this works to people, and how [spirits] will mention people who are living in your life. Friends, family, coworkers, people you like, people you don’t like. They want you to know they’re watching over you. No matter what’s going on, significant or insignificant, they need you to know that somebody who loves you is watching you.”

“Don’t you want to know who’s around you?” Vicki asks me, looking up and over my left shoulder again. “Is it your grandmother? I’m hearing the name Mary.”

Sure, it’s a common name, but one that just so happens to be the birth name of my mother—a name very few people know was her given name by her mother.

“Do twins run in your family?”

I’m lost. No twins that I know of.

Vicki leans closer. “She says, for you, she agrees. She thinks you’ll be one and done with twins.”

It clicks. Only two days ago, I’d met with my two oldest friends over coffee, one of whom has just become an aunt. I’d mentioned offhandedly that I don’t think I’d want to be pregnant more than once, so it had better be twins. It was such a little thing, but hard to brush off as a coincidence on something this specific.

Could any of us become psychics? Can anyone see and hear the same things Vicki does? Now the questions are flooding my mind.

“Everybody has something. You’re born with it, no matter what. Not everybody is psychic, or a medium. Someone may be more in tune to animals or have more extra-sensory perception.”

Can you grow what you were born with?

“Absolutely. I love helping people figure out their gifts. For me, it was usually visual, and I hear them. But for you, for example, maybe it’s a sense of smell, things that move out of the corner of your eye. The signs are there, always. It’s just, do we know what to look for? It’s an amazing thing. We can all be in touch with our gifts if we want to be. All we have to do is be open to the process.”

Catch Monroe at Jonathan’s Ogunquit on November 9.

9: Contrarian

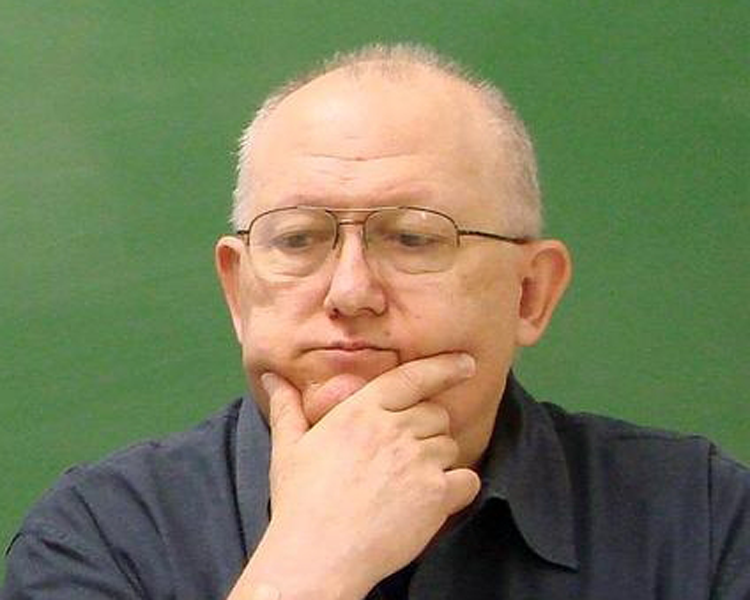

Kenneth A. Capron has A Modest Proposal* for a Cruise-Ship-Sized Problem.

By Colin S. Sargent

Activist founder of MemoryWorks and self-confessed contrarian, Ken Capron, 67, was born in Eastport and is a retired CPA and Microsoft engineer. A former director of accounting at Maine Medical Center, Capron recently proposed plans for the Hope Harbor Project. His vision is to purchase and reconfigure a used cruise ship to provide services and housing capacity to take a direct step toward eliminating homelessness in Maine. We caught up with Capron to get some insight on his approach, because it seems that whatever one thinks of the idea, he’s unquestionably gotten people talking about it.

I would describe myself as a contrarian, an out-of-the-box thinker, and a creative innovator. That’s a challenge no matter where you are, but in Maine as in anywhere it can sometimes be hard to get people to listen.

While working with seniors with dementia, it became obvious to me that there’s a shortage of housing for seniors, especially assisted housing. That affects all seniors, whether they’re healthy or not. It got more and more frustrating to keep running into this issue, so I started to look for alternatives.

The people I met through the dementia program have really given me a heads-up when it comes to homelessness. Many of the problems are similar, and many problems overlap. People in the homeless community might be suffering from dementia—and certainly do at higher rates than the average population. Statewide, there are probably 1,200 people on any given night who need housing and who might not be able to get it: There’s a lack of women’s shelters, youth shelters, and shelters for immigrant populations.

My approach is to always have an alternative solution. The way we’re doing things right now is not working. We keep looking back at the old ways. We have to get rid of that knee-jerk reaction of ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ We have to think in new ways about these old problems.

So, when I say that I’m a contrarian, what I want you to understand is that ANYTHING would be better than leaving things as they are, or paring them down even further. Why haven’t the resources been found yet to fix these problems? People have to remember your problem, the issue you’re working at. In order to break out of the comfort of the status quo, we need to consider the kind of big ideas that will stick in your mind.

I like to think of myself as a systems analyst. After all, my prior careers were as a CPA and Microsoft engineer, so I am trying to analyze the problem of what is going wrong, why our system doesn’t make new solutions. I see how there are bottlenecks that pop up. How do we break through institutional and personal patterns of thinking (as institutions are made out of people)?

If you want to fix an airplane, you don’t do it with a band-aid. You need something much more complex. Housing is a cruise-ship-sized problem. We need an idea on the scale of a cruise ship to address it!

I was impressed, however, to find out there’s a little bit of room for new ideas here in Maine. For example, new thinking has shifted resources away from newcomers to the long-stayers, the cases who they see repeatedly. We want to take this model and expand it so that we can focus on the outcome of turning that number of 1,200 who can’t find housing into zero, over time.

What we want people to understand about our project is that this would be a nearly ready-to-go solution that would be easily refitted into office space, worker housing, homeless housing, and emergency overflow for other underserved populations as we’d need. It’d help us avoid the NIMBY [Not In My Backyard] problem, help us avoid the need to find, get approval, and build a facility on land that might receive understandable protests from those in the immediate vicinity. A converted cruise ship is not unprecedented: emergency temporary refugee housing on ferries and cruise ships is being employed in Europe. [We even sent the Scotia Prince to New Orleans for hurricane relief.]

The number one thing we want people to know about this is that this idea is not a ship of shelter housing, but would instead be an immediate and available set of social service offices including housing that we could rapidly reconfigure. We want to create a one-stop shop for services so that we’d be able to have the greatest impact possible on any residents.

Without external funding, Capron co-founded MemoryWorks with Donna Beveridge out of the desire to create peer-to-peer support networks, based on his concept of ‘memory cafes’ that could supplement the services they experienced after their own diagnoses. Based at 1375 Forest Avenue in Portland, MemoryWorks has grown from a few meetings of volunteer time to a homegrown charity that provides memory screenings and a comfortable entry point for people who, for example, may be undiagnosed but have been having terrifying moments.

Capron has proposed that the ship be docked at the International Marine Terminal. And he challenges every one of us to come up with a better idea that, like his cruise ship, matches the scale of the problem.

* To read Jonathan Swifts’s “A Modest Proposal,”

see http://bit.ly/AModestProposalSwift

10: Style & Stables

As the world beckons, Ariana Rockefeller Bucklin treasures her ties to Mount Desert.

By Sarah Moore

While the Rockefeller name holds international currency, it carries more personal caché in Mount Desert Island, where her family has carved its mark into the physical and cultural landscape. For Ariana Rockefeller Bucklin, granddaughter to Chase Manhattan CEO David Rockefeller (1915-2017) and great-great-granddaughter to patriarch John. D Rockefeller (1839-1937), these shores represent the convergence of families and a love story–she married Colby grad Matthew Bucklin (of Northeast Harbor’s C.E. Bucklin & Sons family business) after a lifetime of shared summers. Ariana and Matthew’s wedding ceremony took place in Abby Aldrich’s historic garden in Seal Harbor.

But after you’ve interned in the office of the secretary general of the United Nations, started your own handbag brand, and competed on the world stage as an equestrian athlete, and grieved for your grandfather who meant the world to you, what do you do? What does it mean to stand on the shoulders of some of the nation’s most prolific entrepreneurs? “I’m at once a member of my family and my own person,” Rockefeller says. “I’ve always considered my heritage both a privilege and an honor.” The Columbia graduate has spent periods of time abroad, in Hawaii and Brazil, perhaps testing the outer reach of her family ties.

Now 35, she divides her time between training as an equestrian show jumper in England and Palm Springs and designing handbags in New York. She insists that the dichotomy of farm life and a cosmopolitan role in fashion are symbiotic. “I have to prioritize and plan out my time in the city between competitions, so I’m always very productive and organized in a short amount of time. In England, I can work on emails before the U.S. wakes up, and before I go to the farm. In the afternoons I’ll schedule calls in for my business [arianrockefeller.com], work until dinnertime, and then early to bed. Technology is certainly helpful!”

Her life of style and stables overlapped earlier this year, “when I was given the chance to design a handbag for the inaugural Longines Masters of New York show jumping competition.” Heir to the Rockefeller success machine, Ariana has a measured view of failure. “You learn through mistakes made and corrected. I’ve learned so much over the years growing my brand and committing myself to an athletic career.” She even adapts a Teddy Roosevelt quote from Man in the Arena: “[S]he who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if [s]he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that [her] place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory or defeat.” This quote hopefully doesn’t relate to the thorough investigation Roosevelt ordered on Rockefeller’s Standard Oil in 1904.

Over 110 years since John Davidson Rockefeller first fell for Mount Desert, Ariana feels the tug of Maine like a homing call. “I’ve spent every summer and almost every Christmas in Maine since I was first brought there at two months old.” Christmas Eve meals on Mount Desert are a Rockefeller tradition that spans generations. The carriage roads that John D. Jr. designed and built between 1913 and 1940 would later ignite his great-granddaughter’s love of horses. “I learned to ride on those trails. My grandfather drove a carriage almost every day during the summer, as did his father. I always loved driving on the carriage roads with Grandpa. I even learned a bit about the sport from Grandpa’s head coachman, Sem Groenewoud, when I wasn’t training with my show jumpers. My Aunt Eileen continues the tradition with her Morgan horses.”

When David Rockefeller passed away last year, the billionaire (whose fortune was estimated at $3.3B) passed a baton of philanthropy down to the younger generation. The Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller sold in its entirety at a charity auction at Christie’s New York for $832.6M, a record-breaking total for a single auction. Ringing Point estate on MDI sold for $19M to charity. Ariana was allowed to choose one keepsake. She picked a bracelet David had once bought for Peggy McGrath. “Losing such a wonderful leader and devoted grandfather was the most difficult change and loss. In terms of material objects, the plan to have the collection and properties go to auction for charity was always part of the family dialogue, so we were well prepared and enthusiastic for those changes.” The young heiress’s own philanthropic passions center on healthy horses and the justice system. “I care a great deal about equine welfare and often work with the Humane Society of the U.S. on equine welfare programs. On a humanitarian level, our family foundation, the David Rockefeller Fund, works extensively in the area of criminal justice. I see this as one of the most important issues facing the United States at this time, one in which we must see policy change.”

What’s the big deal about Acadia?

The close proximity of the mountains to the ocean and granite shores is particularly special. It’s the combination of spruce trees and ocean air that is the most wonderful smell. Of course jumping off the dock into the ocean takes your breath away but then there is nothing more refreshing.

0 Comments