September 2013 | view this story as a .pdf

You’ll be amazed to see how exotic “local” can be.

By Claire Z. Cramer

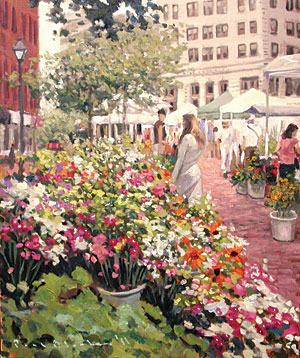

Early on Saturday mornings, a long stretch of tented farm-stand tables snakes through the heart of Deering Oaks Park, heaped with fresh eggs; coolers full of frozen meat; displays of cheeses, honey, pickles, jams, seedlings; and freshly cut flowers. But it’s the best pickings of fresh produce that the home and restaurant cooks are here for before 9 a.m. There are more varieties here than would once have seemed possible.

Early on Saturday mornings, a long stretch of tented farm-stand tables snakes through the heart of Deering Oaks Park, heaped with fresh eggs; coolers full of frozen meat; displays of cheeses, honey, pickles, jams, seedlings; and freshly cut flowers. But it’s the best pickings of fresh produce that the home and restaurant cooks are here for before 9 a.m. There are more varieties here than would once have seemed possible.

International Intrigue

“We love our Jamaican gherkins,” says Mary Ellen Chadd, who’s owned organic Green Spark Farm with her husband Austin for the past three years. “They’re round and prickly, and they grow wild in Jamaica.” Who knew? On this Wednesday in Monument Square, her cukes are small, seedless Europeans. She’s set out bags of young pea shoots, bunches of Thai basil, and half-pint baskets of shiny, bright-green Japanese shishito peppers–jalapeño-sized and ridged like okra pods. “Just sear them in a dry cast-iron pan until they char a bit, pile them on a plate, drizzle them with olive oil, sprinkle sea salt, and pick them up and eat around the seeds.” Curious, I take some home and follow her instructions exactly. Once charred, they look pretty sorry, but I go ahead and apply olive oil and salt and try one. Within a minute, I’ve eaten six. They are crazy delicious and completely unlike any green pepper I’ve tasted. Even better, they’re nearly seedless.

Even the green beans at this small stand are from away–glamorously skinny French haricots verts.

All Hail Kale

“Dinosaur’s the rage these days,” says Bruce Hincks when asked about trends in kale. His Meadowood Farm in Yarmouth grows the wrinkly, oval-leafed Dinosaur, also called Tuscan or Lacinato, that has left old-school, tough, leathery, curly kale suffering in comparison. The dark green Tuscan, tender and less dominating in flavor, is more versatile and quicker to cook. It’s mild enough to cut in shreds, dress with lemon and olive oil, and eat raw as a salad. The farmers’ market is full of the new kales–the flat, lacy Russian and collard-leaf Camden types are tender and mild in flavor; like the Tuscan, they take very little time to cook.

How do farmers choose vegetable varieties to grow? It’s a balance between proven, hardy winners and trying new things. Over the years, I’ve learned to trust their instincts. Will they grow more of something the next year if it’s trendy this year?

“No!” says Freedom Farm’s Daniel Price.

“No!” says Ian Jerolmack of Stonecipher Farm in Bowdoinham. “Everything’s hot for about one minute! I grew puntarelle [an Italian dandelion-like green] last year for a chef. People tried it once and that was it. I was throwing it away.”

Yet Stonecipher grows super-trendy cipollini onions in yellow and red varieties. “Cipollinis store better than I thought, so I planted more this year,” he says.

“Anything Italian sells,” says Hincks, who offers the Rosa di Milano among his onion varieties and claims his ridged Italian zucchini has a superior cooked texture. I try some; he’s right, but it’s still zucchini.

Still Growing

“We bought our 55-acre farm in 2004,” says Daniel Price, who owns it with his wife, Ginger Dermott. “We’re up to five greenhouses now.” Freedom Farm, like Green Spark, Meadowood, and Stonecipher, is certified by the Maine Organic Farmers and Growers Organization (MOFGA). Freedom’s known for its comprehensive selection of crops you never used to find at Maine farmers’ markets: heirloom and French Charentais melons and unusual winter squash; tomatoes of many colors; Asian and Italian eggplants; a variety of onions, including the long red Tropea; fennel bulbs; and a large selection of hot and sweet peppers, including the winning little shishito. “We added the pepper roaster–it’s popular,” he says of the propane-fired, spinning-drum contraption he sets up next to his stand during pepper harvesting season in late summer and fall. Buy a few pounds of peppers and they’ll roast and char them on the spot, saving you the hot work of broiling or grilling them at home. And what peppers! Big oblong reds in varying degrees of heat; fat, sweet bells; hot little red and green varieties; and dark green poblanos. Take home roasted poblanos and your work’s half done to make chiles rellenos.

Freedom is one of many farms growing shallots, formerly wizened little brown imports begrudged a tiny corner in supermarket produce bins. Now they’re common as onions–a healthy, fresh native crop. In the past couple of years, Freedom and a few other farmers also discovered they could grow fresh ginger. Ginger! The fresh roots are pale and rosy before the skins turn brown and dry. The flesh is wondrously juicy and tasty, and the above-ground leaves, still attached, make great tea.

Superstar

Garlic takes the blue ribbon as Maine farmers’ most evolved crop. Ten years ago, you might have occasionally spotted a basket of local garlic and picked up a bulb as a novelty. Nowadays, garlic is a destination attraction, starting with the curly green scapes (tops) in early summer, which can be cut and used in stir-fries, or puréed into a mild pesto. Scapes are closely followed by young garlic bulbs–snowy white with long, hard stems attached and mild, juicy cloves encased in soft, not-yet-papery skin. Then comes the avalanche of cured bulbs. Garlic is so widely available in late summer and fall at the farmers’ market that it’s possible for a home cook to stockpile almost enough to last until the first scapes turn up the following summer.

“I think we grow about 20 varieties [with names like German red and white, Polish red, Siberian red, Georgian fire, and Oregon blue]. Some people come with little Sharpie markers and write the name on each bulb,” says Meadowood’s Bruce Hincks. “They’re serious. They have tastings.” A savvy trend-chaser, Hincks also rides the wave of fancy peppers, offering basket upon basket of long, light green Biscaynes; even lighter green Sweet Banana; bell-shaped Island Purple; Hungarians; shishitos; and many, many small hot chiles. Everyone’s going bananas for peppers. Meadowood has another niche in onions–Italian cipollinis and Rosa di Milanos, mild white Ailsa Craigs, Red Wings, and Walla Wallas.

Traditional Roots

Beets, turnips, and radishes have had their own renaissance. Gone is the disrespect, the dutiful consumption for the sake of the vitamins. The farmers tempt us early in summer with baby-sized red, golden, pink, and candy-striped Chioggia beets–still attached to delicious, tender greens in the weeks before they roll out the bigger and more storage-friendly tennis-ball versions. Salad turnips are pure white–sweet enough to slice and eat raw when they’re still walnut-sized–and they can be seared and braised when they mature. Radishes come in red, pink, pink-topped white “icicles,” golden, and long white Japanese daikons. Restaurants really go to town composing salad plates with all of these jewel-toned roots.

Although not exotic, heirloom tomatoes and potatoes continue to enjoy lavish attention on Maine farms. We want gnarled, asymmetrical Brandywines, Striped Germans, Cherokee Purples, Green Zebras, and Black Princes. We want our first new potatoes smaller than golf balls, and then yellow-fleshed, red-skinned, and fingerling.

“We’ve been coming to Portland’s farmers’ markets for 20 years,” says Carolyn Snell of Snell Family Farm in Buxton. The Snell farm dates to 1926, and it grows especially fine varieties of beans (basic Kentucky Wonders, haricots, flat Italian Romanos) plus shell peas and sugar snaps.

Snell also grows fava beans–this Mediterranean peasant is a recent foreign invader at several stands. Unlike most beauty-queen vegetables that restaurant and home cooks pounce on for their good looks as much as their superior flavor, favas are a harder sell. The pods are big, tough, and homely. You’ll shell a lot of them to net even a modest pile of the large flat beans within. Then you must blanch and peel the leathery skin from each bean. This kind of labor intensity loses a lot of potential buyers, including restaurant chefs. But there’s a reason why farmers grow them. The ecstatically green inner beans–tender, buttery, nutty–have a devoted fan club. Rather than spend all day shelling, blanching, and skinning favas, it’s possible to use just a small amount in a sautéed medley with other beans or peas, or as green accent marks in a pilaf of rice or orzo. Shave on a little Parmegiano Reggiano and you feel like Marcella Hazan, the queen of Italian home cooking.

Farmers’ markets turn you fresh, too. Just try something new.

0 Comments