September 2018 | view this story as a .pdf

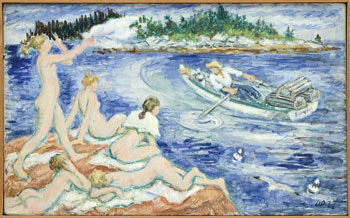

Waldo Peirce, proto-hipster, American Renoir. The more we see him

through his wives, the clearer his life and times become.

By Colin W. Sargent

Rabelaisian, bawdy, witty, robust, wild, lusty, protean, lecherous, luscious, the kind of man Ernest Hemingway wished he could be, Waldo Peirce (1884-1970) is Maine’s satyr prince of the art world. He devoured life. So whatever happened to his wives?

Rabelaisian, bawdy, witty, robust, wild, lusty, protean, lecherous, luscious, the kind of man Ernest Hemingway wished he could be, Waldo Peirce (1884-1970) is Maine’s satyr prince of the art world. He devoured life. So whatever happened to his wives?

It’s well known Waldo was pals with fellow Harvard classmate John Reed (played by Warren Beatty in Reds); ran with the bulls at Pamplona with Hemingway; appeared as a character in The Sun Also Rises; and painted Hemingway across Europe and Key West, one canvas gracing the October 18, 1937, cover of Time magazine.

But it’s not so well known that Waldo’s four wives were doorways for his perceptions. Most survey stories about the strapping six-foot, two-inch Bangor native barely get to his wives, or leave them out entirely. Let’s instead begin with them.

Door No. I

The Wild Child

Dark-haired, dark-eyed Dorothy Rice (1889-1960) was 18 when “Girl on Motor Cycle Laughs at Speedy Police” rocked Manhattan’s society pages in 1907. The heiress was “charged with driving motorcycles on Broadway at 35 mph… Bicycle Policeman Merritt was at Eighty-fifth and Broadway when Miss Rice and her party [of six millionaire teenagers] flashed by him, ‘burning up the asphalt…’ He pursued, but at Ninetieth street was still trailing by a block. Bicycle Policemen Walsh joined him, but the speeding sextette gave them their gasoline odor and dust… Miss Rice made them hustle for 12 blocks.”

Officer Mallon finally “overhauled her at One Hundred and Twelfth street, where he coaxed her to throw out the clutch” on her beloved blue Indian™. “She begged and pleaded, shook her curls and stamped her feet, but Mallon was firm…” Dragged into 100th Street Station, her gang was photographed “in forlorn attitudes.”

But Dorothy wasn’t vanquished. When the patrol wagon arrived to take them all to the courthouse for immediate sentencing, “Miss Rice asked to be allowed to sit beside the driver. Mallon, however, insisted on accompanying her to court on his motorcycle. When arraigned before Magistrate Hoffman her cheeks were radiant and she seemed to enjoy the episode.”

From whence the insouciance? Her father owned Electric Boat. He didn’t just build the Navy’s submarines, he held the patent for them. The Rice kids and their friends were so rich their clubhouse was the St. Regis.

Dorothy studied sculpture and painting in the Art Students League, with private instruction and encouragement from Robert Henri, William Merritt Chase, John Sloan, and George Bellows. These men in capes liked her art, and they didn’t mind her father’s money, either. They suggested a one-artist show. Splashy venue, unbelievable press anticipation, jealousy from other artists. Likely, Dorothy sensed it was time for a new address.

Cruising to Europe, she painted in a castle in Madrid and studied under Joaquín Sorolla when she wasn’t in Paris (she met Rodin at his studio days after the Titanic went down). “My work went very well, partly due to me and partly to my subconscious, which I discovered one morning. I was very tired, so I took strong coffee for breakfast. Coffee always makes me slightly nauseated; it did then, but I had to finish a picture, so I worked anyway. I began to feel worse and worse; I continued working, but practically never looked at my canvas, concentrating entirely on my condition… When [Ignacio] Zuloaga came in he was terrifically impressed. He said it was by far the best picture I’d ever done. From then on, whenever I’d reached the finishing touches, I would drink black coffee and turn the matter over entirely to my subconscious.” Dorothy’s canvases grew close to room size.

Classmate George Biddle introduced her to her future husband during her second winter in Paris, when she was 23. “It seemed he had a friend called Waldo Peirce who, he assured me, was just as crazy as I was,” Dorothy writes in her 1938 autobiography Curiouser and Curiouser. “I was interested… I inquired Waldo’s height—he was six feet two. This seemed a dignified height. I told George to produce Waldo, which he did.

“We got married in Madrid, in a German Methodist Church, with the American vice-consul, who was a Filipino, to make it legal.”

How droll. Why did the world press channel their romance so deeply? To begin with, these sexy ex-pats were a perfect match as risk-takers. Harvard football star Waldo had once hopped aboard a freighter bound for England with classmate John Reed, then dove overboard halfway out of Boston Harbor, leaving Reed to defend himself from charges of Waldo’s “disappearance” and “murder.” Waldo’s punchline for that prank was to meet Reed at the docks when he reached England, having caught a faster ship.

They also shared vast fortunes (for Waldo, it was timber money on both sides of his family). They were a dream couple, with talent overload. Nothing could stop them.

“We lived in Spain in the summer and Paris in the winter, but we fought in both places,” Dorothy writes. “We couldn’t agree who was the better artist. In 1914 Father and Mother and the family were in St. Petersburg. I was on the way up to meet them when the War broke out, so I went with them to England, and then home. Waldo joined an ambulance corps and stayed behind.” In France.

Under the Net

An American Venus

“But while her husband was away, the adventurous Dorothy learned to fly at the Wright School in Mineola, New York, and earned pilot’s license No. 561 from the Aero Club of America on August 23rd, 1916, becoming the tenth woman in the United States to be licensed to fly,” reports check-six.com. Dorothy was seven full years ahead of Amelia Earhart, tearing up the clouds with her dashing flight instructor, a Navy lieutenant junior grade whose dad, Elmer Sperry, had invented the gyro compass. Young Lawrence Sperry used his father’s invention to invent the world’s first turn-and-bank indicator, the world’s first retractable landing gear, and the world’s first autopilot, according to www.check-six.com.

On November 21, 1916, Sperry and Dorothy gave his autopilot a test run while aloft in Dorothy’s “personally owned Curtiss hydroplane… The gyro-stabilizer…was knocked off, and the plane descended into the waters a half mile off the shores of Long Island’s Great South Bay…”

Because such details can be delicate, check-six.com lets Sperry pick up the story: “It was only a trivial mishap. We decided to land on the water and came down perfectly from a height of 600 feet and would have made a perfect landing had not the hull of our machine struck one of the stakes that dot the water, which staved a hole in it.”

Check.six.com resumes: “The [gashed, sinking] plane became entangled in fishing nets” when “a pair of duck hunters who witnessed the plane’s plummet to Earth rowed out to the crash site to help the now waterlogged aviators [hanging onto the debris]. They noticed that both Sperry and [Mrs.] Peirce were naked!

“Sperry quickly stated that the force of the crash ‘divested’ both [himself] and Peirce of their clothing.”

Because ‘accuracy, accuracy, accuracy’ is the watchword for legends of this nature, check-six.com brings the claim home with, “Sperry later confessed to a friend that the duo were involved in the physical act of love, and that he must have accidentally bumped the gyro-stabilizer platform while maneuvering. And although their flight occurred well below 5,280 feet, the pair of lovers are generally recognized as the first members of the Mile High Club. …In the end, in the autumn of 1917, Dorothy Peirce filed for divorce [while Waldo was off winning the Croix de Guerre for his heroism], citing non-support and cruel treatment. Mr. Peirce did little to contest the divorce–and was rather happy to be separated from Dorothy’s mother, whom he referred to as ‘the umbilicus.’”

Dorothy and Waldo were such a dream couple that Psychology Today points to their breakup as an unnerving cultural phenomenon. Newspaper stories from the period grappled with the question of how a relationship between two such perfect—even “eugenic”—individuals could fail. The December 9, 1917, issue of the San Francisco Chronicle included a full page spread on Dorothy and Waldo’s divorce with photographs of the unhappy couple, entitled “The Sad and Very Imperfect Romance of a Perfect Man and Perfect Woman.” The article stated that when Dorothy and Waldo married in 1912, the public saw it as “the test of a new biological theory—the mating of two perfect persons.”

Call them “the beautiful ones.” Things get a shade darker when you consider that according to Waldo’s grandson, Will Peirce of Kittery, a landlord and former assistant to Francis Ford Coppola (including a screenplay draft for Inevitable Grace), Waldo was upset about the way Dorothy broke it off. “I believe my father (Michael Peirce) told me she had an abortion. Waldo was sure it was his child.”

“Dorothy remarried and became a world-class bridge player with her husband, Hal Sims [they met when he chartered her aircraft], until his death in 1949,” writes check-six.com. Even in bridge, she was famous for her “nonconformity…developed during her early childhood,” writes the New York Herald Tribune in her obituary. “She passed away [in Cairo, Egypt] in 1960,” still working as an international political news correspondent.

Among her many achievements, Dorothy wrote the mystery novel Fog, with Valentine Williams. The cruise liner Barbaric, bound for Southhampton from New York, becomes haunted by an icy mist. A murder is discovered. Then a clairvoyant vanishes, sparking a “cycle of fear” among the passengers, who turn on each other.

How Dorothy affected Waldo’s art: Mysterious, intuitive, unapologetic Dorothy elevated Waldo into a stratospheric sphere of clients and opened up his audience to collectors with deep New York pockets. As for her intellectual elan, Dorothy is credited with nothing less than coining the word “psychic.” In bridge, she invented the term “psychic bidding.” Waldo should have known it was dangerous to try his luck.

Door Number II

The Drama Queen

Ivy Troutman (1884–1979) was an actress who appeared “in at least 21 Broadway productions between 1902 and 1945,” according to Wikipedia, many of them long-running hits, one of them, The Late George Apley, a satire on Boston high society co-written by George S. Kaufman and John P. Marquand, running through 384 shows.

Dark and lovely, Ivy traveled to Paris. In August 1920, she married Waldo and moved into his flat at 77 Rue de Lille. She “turned briefly to painting while living in Paris and southern France in the 1920s,” according to the New York Times. “She and her husband were intimates in the small circle of American expatriates that included F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and Ernest Hemingway. ‘Ivy,’ Rosalyne Frelinghuysen, a contemporary, recalled, ‘was the youngest in the salon, so she always poured the tea.’ Both she and Waldo were characters in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, according to Mrs. Frelinghuysen.”

Hemingway had become obsessed with Waldo’s stories. “He may have seen a photo of Waldo in his [uniform] in the Chicago Tribune in 1918… Perhaps this image helped spark Hemingway’s desire to volunteer…” writes Dr. William Gallagher of Bangor, an expert on Waldo Peirce, in the Harvard Review. Gallagher notes that once Hemingway reached the front in northern Italy, “He may not have driven an ambulance very much at all… Hemingway drove an ambulance at most three times. Hemingway ended up distributing candy, cigarettes, and postcards in the Rolling Canteens.”

Many of the bloody, frightening sequences with ambulances that Hemingway is so famous for happened to Waldo Peirce, with Hemingway transmitting Waldo’s larger-than-life stories straight into his work.

“By then, [Waldo and Ivy were dividing their] time among Paris, various locales in France, Hammamet in Tunisia, and trips back to the states for Ivy’s career and his own art shows in New York,” Gallagher writes.

The Kardashians of their day, our expatriates got a lot of ink. Even Ivy’s fender bender was world news, from the New York Times to the Peoria Journal Star: “Paris, July 16 [1929]. – Mrs. Waldo Peirce, wife of the American artist, is resting comfortably at home after injuries in an automobile accident. The automobile in which Mrs. Peirce was riding was greatly damaged but she escaped with slight bruises. She was treated at the Versailles clinic nearby the scene of the accident and went immediately to her home. Mrs. Peirce formerly was Ivy Troutman, noted actress in New York. She married Peirce nine years ago,” but that marriage was not to last.

According to her former paperboy, Jim Forest: “In 1951, Ivy purchased a run-down mansion on Newman Springs Road [in Tinton Falls, New Jersey], a short walk from our house. Built in the mid-19th century, shortly after the Civil War, Ivy presided over a restoration that transformed the near-ruin into a palace. For some reason, she took a special liking to me. The result was that I put Ivy at the end of my newspaper route, as she often invited me to stay for a while. Serving me a small glass of Dubonnet (imported from France but with water added in deference to my age), she often talked about her days as an actress… The First World War took her to Europe to perform for the troops.

“During her Paris years, Ivy had been a close friend of James Joyce. Perhaps the greatest treasure in her treasure-filled house was a copy of the first edition of Joyce’s Ulysses, published by Shakespeare & Company. Joyce had penciled in corrections on nearly every page… Ivy had a breathtaking art collection. I found especially fascinating a small Alexander Calder mobile hanging in the living room and, in a hallway, one of Calder’s large single-line circus drawings. Occasionally Ivy had parties—soirees—for friends living in New York. Though Ivy had a maid, I was asked to put on my Sunday best and serve drinks. The guests were mainly theater people. One of the regular guests was Raymond Burr, eventually to become best known for playing lawyer Perry Mason… The only material gift from her that I still have is a delightful watercolor by Waldo Peirce. Peirce himself is on the left, manfully cutting down a tree, Ivy seductively reclining on the right, and the Maine wilderness, in which Peirce had grown up, in the background. It hangs in our living room.”

Door Number III

ingenue, officer

Ivy was dumped for 22-year-old Alzira Handforth Boehm, granddaughter of Vienna-born August Abraham Boehm, the high-flying developer who built an 11-story skyscraper in the Manhattan Diamond District that was one of the first in the world. Known as 14 Maiden Lane or “The Diamond Exchange,” it’s still there.

Little Miss Skyscraper’s grandfather also worked with Maine native Sir Hiram Maxim to bring gasoline combustion engines to Europe. As in, automobile engines.

Dark and sexy, Alzira studied at the Art Students League in Manhattan and later studied in Paris. As a sideline, “her poetry was published in The New Yorker,” according to Wikipedia. “She taught art,” too, the site says. Among her students: “Gahan Wilson.”

She and Waldo “met at a Matisse show in New York,” Gallagher writes. “Pregnant before Waldo married her, Alzira spent some time in Key West and visited with Hemingway. In 1930, Waldo took Alzira back to Paris where she delivered twin boys in the American Hospital, the very hospital where Waldo often delivered the Verdun wounded.”

They had two sons, Michael and Mellen, and one daughter, Anna. [Mellen Chamberlain Peirce is an active poet and playwright who lives in London. In his 80s, Mellen has been explosively coming out with book after book of new poetry since 2007. His wife is Gareth Peirce, the human rights activist attorney for the Birmingham Six and Gerry Conlon and the Guildford Four. Emma Thompson was nominated for an Oscar playing Gareth in the 1993 movie In The Name of the Father, with Daniel Day-Lewis also nominated for his role as Conlon.]

In 1938, both Alzira and Waldo joined the Works Progress Administration as a husband-and-wife team. Ellsworth’s City Hall is graced by an Alzira mural, Ellsworth, Lumber Port.

During World War II, Alzira was an Army captain in the American Red Cross Motor Corps. When the war was over, she and Waldo divorced. “She moved to New Mexico and worked as an organizer for the United Mine Workers,” according to Wikipedia.

Alzira’s talent, drive, and the children she had with Waldo deeply influenced his art. When Waldo was painting Hemingway in Key West, or sailors dancing at Sloppy Joe’s, Alzira was painting, too, literally and figuratively, at his side. She was painting across generations.

Door Number IV

Mysterious Earth Mother

Every artistic endeavor leaves a door unopened. But here’s a peek at Waldo’s fourth wife, Ellen Antoinette Larsen: “I spoke with my Aunt Karin,” Will Peirce, Waldo’s grandson, writes. “Her mother was Ellen Larsen, born in Minneapolis in 1920, passed away in 2001. She studied art in New York—she painted. A friend of Ellen’s used to model for Waldo, and she and Waldo went to a well-known cafe or restaurant where Ellen waited tables. It was during wartime. The romance started there. She preferred the quiet life in Maine, but she kept a pied-à-terre in Manhattan. After they got married, she modeled for Waldo, as did his kids. There was no escaping that job in our family! Her painting style resembled Waldo’s sometimes. Sometimes it was quite different.”

Art writer Sarah Sargent of Virginia, who knew Waldo and Ellen, dates their marriage to 1946. “They seemed genuinely devoted to each other. She was yin to his yang. A slight, graceful woman, she was quiet, much younger, and a serious painter in her own right. With her, he’d finally met his match, and their 24-year marriage endured until his death.”

Meanwhile, another mysterious bit of flotsam on the internet suggests their creative relationship might have been even deeper: “Waldo Peirce… came to live in Newburyport for a while… They were painting my daughter’s portrait at the time. The same portrait, I might add, that turned out to be something. Waldo would work in the morning and his wife would work on it sometimes in the afternoon. Keep that quiet.”

0 Comments