November 2015

By Dan Domench

Walter Rhodes watched a man get out of a trumpet-orange rag-top Jeep in the hayfield in front of his farmhouse. The engine-idling bass drum kicked one-two, one-two, one-two… Wind blasted the old man as he drew near, with muscular tan legs sticking out of khaki shorts, biceps pushing at the short sleeves of a faded red T-shirt. The guy had to be in his 70s, carrying a magazine in his right hand, walking toward Walter’s screen door with a side-to-side gait that said I don’t fall or stumble. Sea legs.

Walter Rhodes watched a man get out of a trumpet-orange rag-top Jeep in the hayfield in front of his farmhouse. The engine-idling bass drum kicked one-two, one-two, one-two… Wind blasted the old man as he drew near, with muscular tan legs sticking out of khaki shorts, biceps pushing at the short sleeves of a faded red T-shirt. The guy had to be in his 70s, carrying a magazine in his right hand, walking toward Walter’s screen door with a side-to-side gait that said I don’t fall or stumble. Sea legs.

Walter caught a glimpse of the cover of the magazine. There was a one-page interview in there. Walter read it months ago and read it again as it blinked once at the back of his eyes.

Walter Rhodes Hears Beats And Does Not Run Over Neighbors

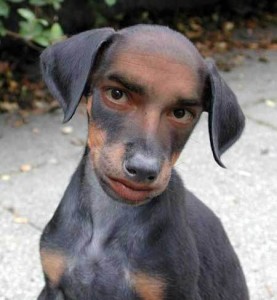

Since his graduate show secretly sold out at The Art Institute of Boston (now the College of Art and Design at Lesley University), the prolific and reclusive Walter Rhodes has attracted avid collectors first in Boston at The Liis Holmes Gallery, then in New York for McRoan and Theodore, and now at Justin Hallgate Gallery in New York and London. His early figurative work seemed like frame captures from an unknown movie you suddenly needed to see. His new work manipulates popular and found images with text that feels absurdly real.

After your “Lost Dogs” solo show sold out this spring at Hallgate London, Justin Hallgate joked that the buyers were all sad dog owners.

Have you met him? He’s a comedian. It’s the perfect gallery for me.

Do you have a dog?

I couldn’t handle the responsibility.

Lucinda Agan of The New York Times said your show at Hallgate New York was hilarious and oddly moving. Did you use flyers and posters of actual lost dogs for the paintings?

People have come into the gallery adamant that their missing dog is the one in a painting, like I’m hiding it in the studio or had it stuffed as a model. Dogs control people willfully. Ever been in someone’s home and a dog walks into the room and the conversation stops while everyone pets the dog and makes dog baby talk? The dog seems almost ashamed of its power.

Bernard Rossi has said he did lost dog portraits before you and you are ripping him off.

I am embarrassed to say I don’t know who he is. I don’t reject other artists. I am a minnow. I got to 1990 in art history and stopped. I can barely get out of the studio, cross the yard, and get into the house for a sandwich. I am borderline agoraphobic, maybe not so borderline. I heard someone say there are two kinds of baseball players, those who know the statistics and follow every player and every team. They play great and make great coaches and teachers. Then there are those who can only play. That’s me. I’m going to die in the studio.

Not from old age anytime soon. You’re 29 years old. Maybe you will get out more later.

I’m 30. I don’t see that happening. I am not going to name the small town where I live, but I am the last house on a three-mile spit of land between two tributaries of the Dead River. There are four other houses on the road. Sometimes my neighbors stand in middle of the road so I have to stop. It’s like talk to me or run me over. Justin calls to check on me or schedule a pickup, but mostly I don’t answer and he leaves a message. A carpenter comes in and builds frames and stretches canvas for me in the barn. She orders paint and supplies and hauls them in. I don’t see her much, but I hear the whine of her saw and it bothers me. I am at the maximum amount of people I can bear.

The descriptions you wrote under the dog’s portraits are humorous in a weird, sad way. I loved the line under the portrait of a not-so-smart looking poodle: “Last seen following a turkey into the woods. Please help.” I could see it as a full-page cartoon in The New Yorker. Have you thought of writing comics or films?

I journal at night, but I don’t think in stories. I look at an image and I hear beats. I’m not happy unless I get four, five beats in a frame. That’s why I add the words and exaggerate the way they look, like scratches from a felt tip marker or ballpoint pen smears but magnified so your eye knows it can’t be right and gets pulled around the words and you hear them differently. I need more beats or I get bored.

It has been reported there are over a hundred of your large lost dog paintings and as many studies. You are prolific. How do you do it?

I don’t consider myself prolific at all. I wish I had a voice like Basquiat. He could rip through canvases, roll around on them on the floor, and they sang. It took me about ten days to do a large dog painting, and I had five or more going at once. I averaged a finish about every two weeks. A study took me a day or more. Three years of lost dogs is enough.

I have to ask, did you lose a dog when you were a kid?

I had a dog who was taken from me by my mother. I could have made that up to make this interview interesting, but it happens to be true. An autobiographical nugget for graduate students. I did the dog series because I want to run away, but I’m too scared.

The old man walked toward the screen like he was going to walk through it and then stopped. “I’m Billy Haig,” the man said, “a friend of your father’s. I’m here to take you to him.”

“To Tom?” Walter said, squinting down at him.

“That your stepfather?” Billy said. “No, your real father. Robert Rhodes.”

“We don’t talk. How’d you find me?”

“We don’t…? For Christ’s sake,” Billy said. “Like it’s a mutual thing. He’s written to you hundreds of times. Okay. I have to keep in mind you’re a little special. You told people where to find you in here.” He rolled up the magazine and pointed it at Walter. “Not many places on the Dead River like you described. I brought it to make sure I got the guy in the photo, and I do. Pack some clothes. We’ll be gone for a few days, and I’ll bring you back safe and still nutty.”

“I’m not going anywhere. I get sick.”

“I’m a doctor, and you’ll be fine. Invite me in.” Billy pulled the screen door open and pushed past Walter into the house. “Looks like a flea market. Nothing in here a good fire wouldn’t fix. Get your toothbrush, whatever.”

“You leave.”

“You’re coming with me to say goodbye to your father who is dying and never stopped caring about you. Because you want to.” Billy was walking toward a chair and lowering himself as he approached it. He was almost fully sitting before his rear hit the seat and he dropped the magazine to the floor.

“No,” Walter said.

“Yes. Because I have something you want. Actually many things you’ll want to add to your fuck-all collection in here. You come with me and be kind to your father and you’ll get them.”

Walter was standing at the screen door, turned only slightly sideways to watch Billy, and because he could very often accurately predict the next note in even the most dissonant of compositions, a grimace seized his face like rock lichen.

“I have your graduate thesis paintings,” Billy said, “most of the work on wood panels that sold at Holmes and a good portion of your early New York canvases. After that you were selling on your own well enough so I could stop buying. Couldn’t afford to continue, anyway. I drove the prices up too high.”

Walter felt displaced. That’s what a therapist had called it long ago, “Displacement.” He floated around in an anxious dream most of the time. Nothing he could do about that. But this, this was knees sickly weak, mind crashing through possible outcomes, all of them painful. He set his feet wider apart.

“Your father is the best man I have ever known,” Billy said. “You have no idea what he has done for you. It won’t kill you to say goodbye to him, to let him see your face. I never had kids so I don’t know why the hell he gives a shit about you, but he does. Now get your stuff and I’ll explain in the car.”

But no explanation was necessary, was it? The one thing that lifted him above his peers at the Institute–the one solid undeniable artistic truth–was that Walter Rhodes sold paintings. One after another. Anonymous collectors. Private buyers on the phone. Strangers walking in the gallery and walking out cash-and-carry. Gallery owners looked at him and turned their heads sideways as if hearing a tone others could not. He had the farm, the studio, time to work, all due to that phenomenon. He should be grateful or mad or something, but instead he felt an acidic hunger. He wanted his paintings back, and the man who had them was sitting slouched in his favorite fat armchair, watching him.

Walter walked into the bedroom and pushed underwear, socks and shirts into a pink princess backpack. The rhinestone sparkles gave it a calming tinkling melody. He slung it on his shoulder and walked through the house toward the rumbling Jeep.

“Good boy,” Billy said.

0 Comments