October 2015 | View this story as a .pdf

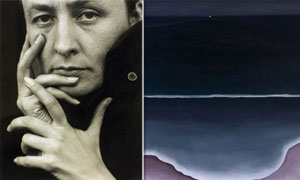

Georgia O’Keeffe’s extraordinary York Beach paintings spanning 1922-1928 are part of her tumultuous love affair with life.

By Colin W. Sargent

The sense of “Made in Maine” shapeshifts in front of our eyes. But Georgia O’Keeffe, a Maine painter?

The sense of “Made in Maine” shapeshifts in front of our eyes. But Georgia O’Keeffe, a Maine painter?

All you have to do is look at her 1928 painting Wave, Night to feel it. Between 1920 and 1928, O’Keeffe vacationed at a seaside guest house on Long Sands Beach in York for inspiration. It was here, in Maine, during torrid separations from her lover/mentor Alfred Stieglitz, that she not only painted Wave, Night but also first experienced the breakthrough that led her to paint sea shells, with their curves and involutions, distances and intimacies.

Vividly, her letters from York Beach to Stieglitz appear in the book My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: Volume One, 1915-1933 (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library). They’re deeply personal and take us straight to her creative essence. As Hervé Fornieri (yes, the French performer) writes in his Amazon review of the collection, “The two most amazing letters in this book demonstrate the almost supernatural synchronicity between these two lovers and artists. The letters were written by O’Keeffe and Stieglitz on the same day, September 25, 1923, while she was visiting York Beach, Maine, and he was staying at their summer home at Lake George, New York, two hundred miles away. Unbeknownst to the other, of course, each had been utterly entranced by the same moonlit night–but O’Keeffe saw a colorful painting, and Stieglitz saw a black-and-white photograph.

“O’Keeffe: ‘Last evening–walking on the beach at sunset I saw a pink moon–nearly full–grow out of the gray over the green sea–till it made a pink streak on the water–very faint–that told you where the ocean began and the soft gray blur of space was ended–And the moon grew hotter and hotter–and the path on the water brighter and brighter till it burned so that I didn’t want to look anymore…’

“Stieglitz: ‘It was a marvelous night. A white moonlight night. I never saw any night quite like it–none more beautiful–For a long while before going to bed I stood at your window looking lakeward–looking at the white silences–the white night so silent. Nothing stirred. Even the moon full & round seemed not to wish to disturb the stillness–it seemed to be moving slowly upwards as if on tiptoes moving through a house of stillness at night when all inmates were fast asleep. All was so still–& the whiteness so lovely–The hills were not hills–they were something bathed in an untouchable spirit of light–the line produced where this spirit met the sky spirit was of rarest subtle beauty–Really I never saw anything quite so beautiful–I looked & looked & knew I was awake…’”

“In 1927 she went alone to York Beach,” Roxana Robinson, author of Georgia O’Keeffe, A Life, shares. “It was a difficult time for her, as Stieglitz was deep in a relationship with Dorothy Norman. This was painful for O’Keeffe, and she left. Stieglitz went to find her there, the only time he ever visited the place.”

His race to Maine was made easier because he was acquainted with Bennet and Marnie Schauffler [and Bennet’s parents, Charles and Florence Schauffler], who ran the guest house where O’Keeffe was staying, in today’s geography near the Anchorage Inn and the Sea Latch. Robinson describes the view from the house as follows: “For Georgia, the trip to Maine was a revelation. Standing at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, she felt again the bliss of a wide flat horizon, the sense of boundlessness and solitude that she had valued in Texas. The house was set with a cranberry bog between it and the ocean, with a boardwalk leading to the wide, clean beach. The house pleased Georgia: nearly empty, spare and plain, with good, old rugs on the floors. Her own room looked out onto the ocean and the dawn. It held a big bed and a fireplace, stacked with birch logs. Georgia spent her days walking on the long, windy, empty beach, scavenging for odd bits that she brought back, set in platters of water, and painted. In the evening she watched for the lighthouse to begin its quiet, comforting rhythm across the nighttime sky and the wide, darkening beach, the deep black water.”

Because O’Keeffe describes the lighthouse as far away on the horizon in one of her letters; it can only be Boon Island light. Considering the elastic curves of her art, it’s hard not to think of her stopping by the Goldenrod luncheonette–already decades old–watching spellbound as the taffy was stretched in the windows, and shyly walking in to buy candy kisses.

In all, there were “four York Beach pictures,” according to Robinson. During this extraordinary period of psychic recovery and self-interrogation, she gathered herself to stun the art world. “From Georgia’s four weeks in Maine the haunting shell series was produced… [Her] ruminations on the theme of the shell range from the highly representational to the purely abstract. Most powerful are the clamshells, open and closed: small works, monumental images. In these, the clamshell’s seam is centered in the narrow perpendicular space. The sense of monumentality is achieved by the space given to the shell within the rectangle: the smooth enigmatic curves dominate, filling it entirely except for the corners…

“It is possible to argue the vulval nature of these images–they are, it is true, interior chambers lined with soft and intimate surfaces. More central to their meaning, however, seems to be their essential qualities of openness and closedness. The cool inevitability of a closed shell, the quiet suspense of a barely opened one, are qualities far more compelling than a purely sexual interpretation would permit…”

Other shell images bring to mind the inner ear, where you can almost hear these paintings. “Whether or not the series was meant to parallel O’Keeffe’s swift and absolute removal from Alfred–her insistent solitude and distance–the quiet shells made a potent statement,” Robinson says. “Numinous, serene, and dignified, they are compelling and mysterious images, enormously powerful, which resonate with a sense of privacy, intimacy, and inner strength. If she was becoming increasingly aware of the threat posed by Alfred’s presence in her life, she was beginning to perceive her own strengths in response to that threat.”

When we contacted Robinson about Night, A Wave, she ventured its value at “several million” and commented, “The painting is extraordinary. I have stood in front of it for a long time; you tend to get lost in it. The effect is mesmerizing, as you lose your understanding of placement. I don’t know another painting like it. In it O’Keeffe manipulates space and perception in a way that is profoundly sophisticated but also deeply moving, intellectually challenging and emotionally engaging. She interrogates the understanding of perception here, eliminating the ideas of foreground and distance without losing a sense of position. It is remarkably powerful in its combination of mystery and command. I’m not sure that it was a turning point; it was part of what she explored all her life–the sense of human relationship to the larger landscape, the balancing of man and nature, the sense of cosmic distance and deep velvety presence. It’s one of her most powerful works.

Georgia O’Keeffe didn’t just paint sea shells by the sea shore, she took great risks at York Beach and made its psychic geography her own. Georgia O’Keeffe a Mainer? Finestkind.

0 Comments