October 2018 | view this story as a .pdf

So much of the history behind these fading buildings is lost to time—but not all.

By Sofia Voltin

“If that house could talk, what stories would it tell?” Kimberlee Bennett, author of Paddling Southern Maine, asks as her kayak floats past a dilapidated cabin on the water’s edge of Upper Pleasant Pond in Richmond. Bennett is known as Maine Kayak Girl across social media. As she explores and documents the waterways, she finds herself face to face with Maine’s ruins. There’s something about a building in disarray—its roof caving in and walls buckling—that sparks curiosity among us, including Bennett and the local explorers she guides. “I wonder who lived there, if they loved the water as much as I do, and if they appreciated having a place on the water. I also see them and feel some sadness. I think about how that came to be. Why were they not maintained or cherished?” These disintegrating vistas echo piercing cries from the heart.

“If that house could talk, what stories would it tell?” Kimberlee Bennett, author of Paddling Southern Maine, asks as her kayak floats past a dilapidated cabin on the water’s edge of Upper Pleasant Pond in Richmond. Bennett is known as Maine Kayak Girl across social media. As she explores and documents the waterways, she finds herself face to face with Maine’s ruins. There’s something about a building in disarray—its roof caving in and walls buckling—that sparks curiosity among us, including Bennett and the local explorers she guides. “I wonder who lived there, if they loved the water as much as I do, and if they appreciated having a place on the water. I also see them and feel some sadness. I think about how that came to be. Why were they not maintained or cherished?” These disintegrating vistas echo piercing cries from the heart.

Exploring and photographing abandoned, man-made structures is known as urban exploration–“urbex” for short. The beauty of nature reclaiming these structures touches thousands in the online groups dedicated to the celebration of these forlorn places.

“When you see an old, abandoned house you don’t know much about, you’re left to your imagination,” David Fiske says. We share a need to trespass, to open that creaking, rusty door. Fiske, the author of Forgotten on the Kennebec: Abandoned Places and Quirky People, manages the Facebook group Abandoned Maine. “You can go to some old house, and it spurs the imagination. These people had high hopes when they built these buildings. Looking at them now, it’s poignant.”

Buckman Tavern, FalmouthMiddle Road once boasted a busy inn called Buckman Tavern. “It was built in 1776 by Samuel Buckman,” Ann Gagnon at Falmouth Historical Society says. “The tavern was a stop along the King’s Highway that ran between Portsmouth and Bangor. The stagecoach stops were usually nine miles apart, and it’d take about a full day to travel.”

Buckman Tavern, FalmouthMiddle Road once boasted a busy inn called Buckman Tavern. “It was built in 1776 by Samuel Buckman,” Ann Gagnon at Falmouth Historical Society says. “The tavern was a stop along the King’s Highway that ran between Portsmouth and Bangor. The stagecoach stops were usually nine miles apart, and it’d take about a full day to travel.”

The inn has inspired tales of terror, including the story of an insane guest who murdered his traveling companion. As legend has it, he tossed the head out a top-floor window. Now every time a well-wisher tries to replace that particular pane of glass, it breaks shortly after.

Neighbors Kathleen and Stephen Daigel say they haven’t been privy to any of these so-called hauntings. Strange, considering the deed to their home states that bodies are buried at the bottom of an old well on the property. Their home was once a part of the stables serving the Buckman Tavern. The well has since been filled in; a stone outline is all that remains to mark the site. “Apparently,” Kathleen says, “whenever a guest died overnight at the inn they had to do something with the body. So they dumped them into the well.” No vacancy at Buckman? No problem.

Town assessment: $142,000.

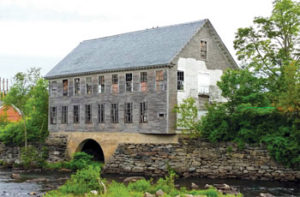

Moulton Mill, West Newfield

Moulton Mill, West Newfield

The Moulton Mill, originally Adam’s Sawmill, was built in 1790. Purchased by Charles Moulton in 1882, the mill on the pond remained in use into the 1980s. “The state made us shut it down in 1986 because of all the sawdust washing down the river,” Edward Moulton, the current owner of Moulton Lumber and great-grandson to Charles Moulton, says. “We didn’t want to take care of the building anymore, so we sold it to Anthony Tedeschi from Limerick in 1995. He had plans to refinish the mill into a museum, but with all the rotting wood, it turned out to be cost-prohibitive in the end.”

The mill is dangerous for trespassers, but photos from urbex groups prove warnings have been ignored. “When we still had it, we lost a lot of antiques to trespassers,” Moulton says. “Back then, we didn’t have the ‘no trespassing’ signs up yet.

Town assessment: $78,600.

U.S. Customs Station, Houlton

U.S. Customs Station, Houlton

“It looks absolutely terrible. It’s completely run down,” historian Leigh Cummings says of the former customs building at 16 Border Lane. “I’ve seen images of the building printed on linen postcards from the 1920s and 1930s. I suspect it was built around 1906. During that period, we cracked down on immigration to the U.S. Sound familiar?”

“The old customs building is boarded up,” says Anthony Coldwell, manager of Houlton Duty Free Station. “We were looking to demolish it, but with the asbestos inside, it was going to be a lot of money. The town decided we could board it up to keep people out.”

According to Bangor Daily News, the current station was built along Interstate 95 on October 25, 1985, with the completion of New Brunswick Route 95. The newly constructed crossing subsequently closed the U.S. Route 2 facility. Cast off like an old shoe, the old place has now been left empty for 33 years.

“Something unique about this spot is, it’s the starting point of Route 2, which continues all the way across the country to Washington,” Cummings says. “The new border station is the starting point for Route 1. There are three blocks in downtown Houlton where U.S. Route 1 and 2 merge and cross the same bridge. This is the only place in America where you can stand on both Routes 1 and 2 at the same time.”

Town assessment: $65,300.

Milo Textile Company Mill, Milo

Milo Textile Company Mill, Milo

Unnerving in its silence, this vast emptiness on the Sebec River has had a “varied history,” Allen Monroe of Milo Historical Society says. “In 1879, Boston Excelsior Company purchased the building for the manufacturing of many different wood products.” The mill was eventually bought by the Milo Textile Company, “which produced yarn and similar products starting in 1922.”

“In its heyday, [the Milo Textile Company] employed about 70 people.” Today, the mill remains a remnant of industrial times now long past. “It’s not being used. There’s nothing in it, but whoever owns it must be paying their taxes.”

That owner was Leon A. Cousins of East Millinocket, who died in 2013. Lilia Cousins says her husband bought the mill a while back with plans to use the barn on the property. “He never got around to doing what he wanted.” Lilia currently has no plans for the building, but recognizes its beauty.

Town assessment (both buildings and land): $33,870.

Moir Farm, Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Moir Farm, Allagash Wilderness Waterway

This old farmstead was first settled in the mid-1800s by George Moir and his wife Lucinda (Diamond) Moir “after the Native Americans moved elsewhere,” according to the website of the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands. (Though the ‘moving’ of Native Americans and the settling of colonists aren’t exactly isolated events.) George and Lucinda raised a family of seven children on the farmstead, and the land remained in their family until 1906.

Their only son, Thomas Moir, sold it to Frank W. Mallet, M.O. Brown, and Charles B. Harmon for the sum of $2,500. Henry and Alice Taylor acquired the property from them shortly after. Henry built sporting camps along the riverbanks, and during the decades he was there, he used the Moir house as a barn and hay shed.

Marguerite Dusha, the Taylors’ granddaughter, remembers visiting her “pioneer” grandparents twice a year at the camps. “I loved waking up early and finding a moose or deer feeding in the field next to the camp. I loved the smell of the spruce trees, the sound of the river flowing by the camp, and the call of the various birds. I enjoyed hiking into the woods and swimming in the river.”

As a Maine guide and game warden, Henry Taylor had plenty adventures to share.“I’d sit and listen to stories of his hunting and fishing adventures every night on the porch of the main cabin,” Dusha says. “I recall several stories of him having a near death experiences from breaking through ice with snowshoes on, to getting caught in a winter storm while trying to fly his plane out, to breaking his leg when he was at camp at the age of 87.”

When the state of Maine acquired the lands that now make up the Allagash Wilderness Waterway in 1966, Taylor was permitted to stay with his cabins. He and Alice spent summers at the camps with guests and family members well into the 1980s. Eventually, the Taylor camps went to seed but have since been restored. The original Moir farmhouse is still (barely) standing. “The last time I was there was in 1993,” Dusha says. “The camps were in disrepair, as my grandfather had died in 1984, but the memories were as vivid as the remaining carved names of all who had stayed in the camp years before. It was a bittersweet visit, as I’d thought it would be my last visit there.”

0 Comments