September 2010

Note to New Yorkers: We also have a claim as a Hopper inspiration.

By Colin W. Sargent

In 1927, Edward Hopper and his wife Josephine Nivison bought a used 1925 Dodge and felt a rush of freedom as they left Washington Square in New York City and headed up the coast of Maine. When they saw the village of Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth, they pulled to the side of the road and took a deep breath. It was here he and Jo, a talented artist herself and fellow student of Robert Henri, spent three consecutive summers, painting the lighthouses and–a tantalizing possibility–stumbling on his inspiration for the breakthrough urban landscape Chop Suey (1929), which up until now has been ascribed to Columbus Circle in Manhattan.

In 1927, Edward Hopper and his wife Josephine Nivison bought a used 1925 Dodge and felt a rush of freedom as they left Washington Square in New York City and headed up the coast of Maine. When they saw the village of Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth, they pulled to the side of the road and took a deep breath. It was here he and Jo, a talented artist herself and fellow student of Robert Henri, spent three consecutive summers, painting the lighthouses and–a tantalizing possibility–stumbling on his inspiration for the breakthrough urban landscape Chop Suey (1929), which up until now has been ascribed to Columbus Circle in Manhattan.

Consider the case for Portland:

ONE: Hopper was here, not in New York, during the summer of 1927, the painting’s gestation period. In fact, he and Jo were frequent visitors to Portland at night while summering at Two Lights. It’s hard to imagine they’d have avoided the new State Theatre (1927)–both were movie and theater lovers–and Eastland Park Hotel (1927), the largest hotel north of Boston, which crowned the Forest City’s theater district along our Great White Way, where the iconic restaurant Empire Chop Suey held sway with its striking incandescent sign.

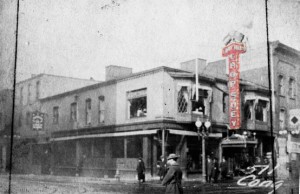

TWO: Location, location, location. John Whipple, of Whipple–Callender Architects, says, “I was the architectural consultant on a committee that reviewed applications for the city’s facade grant program. One of the applications was from Bill Umbel. He wanted to reproduce a large blade sign for his club, the Empire Dine and Dance, on 575 Congress Street, and he needed an exemption from the usual restrictions in sign size. His argument was that the original sign was huge. Scott Hanson was the city’s historical consultant. He showed up at the next meeting with a permit dated August, 1930 that he’d dug out of the city’s files and some photos of the building taken in 1924. The permit was for strengthening an existing sign that was 24-feet tall, weighed 600 pounds, and swung dangerously over the sidewalk. The photos showed a building with two bay windows and a sign with light bulbs that spelled ‘Chop Suey’ in vertical letters. Scott opened a book to Hopper’s painting. We all agreed that if you were looking out the western-most bay window you would have seen exactly what Hopper painted.

“A few weeks later, I told my brother, a painter in Seattle, what Scott had found. He said he’d just helped with a show on Edward Hopper at Seattle Art Museum. The show’s catalog described Hopper’s New York influences at length. We contacted the curator, Patti Junker, and Scott sent her the permits, the photos, and an article by [Maine historian] Gary Libby about Chinese restaurants in Portland. She emailed back: ‘I admit I was skeptical, but after seeing the image, I am absolutely convinced. I think it was this chop-suey restaurant that he had in mind, although the picture was conceived in his studio

in NYC.’”

THREE: To bay or not to bay! The site traditionally ascribed to Chop Suey–a long-lost second-floor joint on Columbus Circle above a Child’s restaurant in Manhattan–lacks the distinctive bay window in Hopper’s painting, while Portland has it. Add that to Portland’s identical distance between windows, and…

Avis Berman, who’s written about Chop Suey for Smithsonian magazine, tells us, “I certainly think there’s credence to your notion that the Maine Chinese restaurant could have sparked Hopper’s idea.”

Gail Levin, author of Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, allows, “He often combined images that he saw in more than one place, so your place might have contributed to his painting even if he ate at the Columbus Circle place.”

Not that Hopper’s talking. Was it a photo or simply a mind’s-eye sketch he drew here? Jo once wrote, “Sometimes talking to Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well, except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.”

Critics point to Chop Suey as a breakthrough. There’s agreement that the seated woman in the cloche hat facing the viewer is based on Jo. More fascinating, the identical diner facing her is, by many accounts, a doppelgänger, making this painting an enlightened comment on the mass-market loneliness of our 20th-century crowds. Or should we call her a “hoppelgänger”?

John Updike gets credit for the insight that “Hopper is always on the verge of telling a story.” Isn’t it wonderful to think each of us might be living out Chop Suey’s narrative in Portland today?

0 Comments