September 2015 | view this story as a .pdf

Singer songwriter Jonathan Edwards makes his home in Maine.

Interview by Colin W. Sargent

It’s a crisp afternoon in the Spurwink section on the Cape Elizabeth coast. What invisible hand is conducting us inland from Route 77 and the Spurwink Meeting House, only to slow to a stop in front of an understated sage-green ranch house in broad daylight?

It’s a crisp afternoon in the Spurwink section on the Cape Elizabeth coast. What invisible hand is conducting us inland from Route 77 and the Spurwink Meeting House, only to slow to a stop in front of an understated sage-green ranch house in broad daylight?

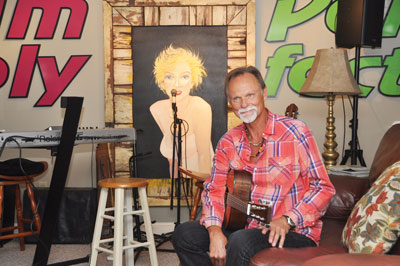

Surprise: Jonathan Edwards, the folk star who brought us “Sunshine” during the darkest days of the Vietnam War, lives here. With an Ed Harris intensity to his eyes, he welcomes us at the door and leads us barefoot downstairs to his studio through a maze of photos and awards to a comfortable leather couch. Like a shadow, his dog Holly, jumps up beside him. Through the windows, in squares of green, are the raised beds of the Victory garden we’ve heard he prizes out back. First impression: He doesn’t look like a marathon runner who’s just finished a race. He’s about to start one.

You’re from Northern Minnesota. Can you show me something in this house that proves that?

He gets up and returns with a haunting black-and-white photo of a young woman in the late 1940s holding a guitar.

This is from Minnesota. It’s a picture of my [birth] mom. I was adopted when I was nine months old. This other snapshot is me. It was taken the day I was adopted. It’s the cover of my new album, Tomorrow’s Child.

Edwards, seated on his kiddie seat with the furious seriousness of the very young, extends both hands toward the viewer, searching. Produced by Darrell Scott and accompanied by Nashville cats Vince Gill, Jerry Douglas, Shawn Colvin, and Alison Krauss, the album is Edwards’s springboard to live performances that will zigzag across venues vast and intimate: Stonington Opera House in Maine; Birchmere, in Alexandria, Virginia; Timberline Lodge Amphitheater, in Government Camp, Oregon; and One Longfellow Square in Portland, September 9 and 10.

Searching seems to be a motif in Tomorrow’s Child.

Yes. Everything I do comes to bear on what I do and what I write.

One of the striking songs on your new CD is “I Wish I Was A Mole In The Ground,” written and recorded in 1928 by Bascom Lamar Lunsford. It tunnels into your memory, has North Carolina roots, is gently subversive. Is that what attracted you to it?

I wish I was a mole in the ground

Yes, I wish I was a mole in the ground

If I’s a mole in the ground I’d root that mountain down

And I wish I was a mole in the ground.

This song just spoke to me. Joe Walsh, who lives in Portland, is on the board at One Longfellow Square and teaches at Berklee [College of Music in Boston], suggested he arrange it and I record it. It’s about heartbreak, sadness, and defiance.

When James Taylor’s new album was released this summer, it topped the Billboard 200. It was hard not to think, they’re looking for a new Tony Bennett.

I enjoy the audiences, period. Sometimes I’ll look out and say, “I see a lot of old people in the audience.” Then I’ll speak to the new members. “Thanks very much for bringing your parents.”

Jonathan’s fiancée, Sandy Owen, says: “This is a good time to mention Jonathan’s album is number one on the folk charts.”

Sandy is a Kennebunk native; they met during a concert in Blue Hill, at an old club called The Left Bank. Edwards says, “I saw her in the crowd.” They talked after the concert, grew closer upon further meetings after years passed. She seems already in deep harmony with him; there’s a rhythm to their motions.

Edwards: I had to decide I was ready for this. I take better care of myself than I ever did. There’s going to be a lot of touring this year.

A colleague saw you perform in Newport, Rhode Island, decades ago. Take us there.

It was a little tiny club twice the size of this room. It was right across from the harbor. I totally felt at home there. I met Cheryl Wheeler there. She’s a friend. Also in Newport, I played aboard a ship, the Black Pearl. I was there for a week. That’s where I got sailing in my blood, after I met Barclay Warburton.

Do you have a boat now?

No time to dream of doing that.

If there were a cocktail called the Jonathan Edwards, how would a 21st century mixologist shake you up? Some folk, a dash of balladeer, some bitters?

(A quick smile.) I’m not so sure about bitters. I’m not preaching the horrors, not me.

So you share nothing with the scary Calvinistic theologian of the same name?

Nothing.

Dark rum then, for the drink called the Jonathan Edwards?

No dark rum. In the late 1970s I used to live in St. Croix, where they serve light rum. I got used to it.

What do you like about playing at Jonathan’s in Ogunquit?

Everything about the venue I like. I’ve been 20 years playing there. Jonathan West is a dear friend.

According to urban legend, you almost didn’t get to record your monster hit single.

It was late one night, in the early a.m. We were recording an album, and the sound engineer and I were the only ones in the studio. Recording [with magnetic tapes] was very young then. He inadvertently recorded over one of the songs he’d spent the afternoon recording. He looked for it everywhere, everywhere. Ironically, the song was called “Please Find Me.” Finally he gave up and said, Do you have something else that’s three minutes long? I said, yeah. A last-minute substitution. I recorded it with the bass, came back and added the track with my 12-string, then a third track with drums. It was “Sunshine.”

What are your 30 best seconds in show business?

I’m standing at the foot of the Washington Monument in 1971, at a huge anti-war rally. It was a rose-colored dawn in the Potomac River Valley. I had just written “Sunshine.” People had just started hearing it. [He waits two beats.] That song was the perfect song to play that morning.

What are your worst 30 seconds in show business?

I was opening for Pat Sky at Boston University or BC. As I neared the stage, a guy in the audience yelled, You suck. What to do? You do the best you can. At the microphone I said, Thank you very much. Usually they don’t say that until I’ve played three or four songs.

Tell us one time you were forced to play “Sunshine” when you didn’t want to.

There’s never been a time. I have always been one-hundred-percent grateful. If I had never had another song, I’d be thrilled to leave this world remembered for that one song.

Sandy Owen hands Edwards a glass of water. (This is a good sign, because it means he’s going to sing, right here in the basement studio of his home in Cape Elizabeth.)

He slings the guitar around his neck and sings it stunningly it like he just wrote it for five people. Better than the first time anybody ever heard it. The day before, he’d sung live on NPR’s World Cafe. Some guys have all the talent.

You know so many fellow musicians. How about Paul McCartney?

I haven’t met him, but I want him to hear my version of “She Loves You.”

Can we hear it?

It seems impossible, to cover that song. The Mt. Everest of cover challenges. How could he possibly make it his own? Then Edwards starts singing, and it’s so wistful and lonely the way he plays it, it makes your hair stand on end. It’s track number five on his album My Love Will Keep (2011). To hear it, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9075lmLck8.

Where’d you go after you lived in Boston?

In 1973, I lived in Nova Scotia, farming 680 acres. I lived there for eight years. My daughter Grace was born at the top of a hill in our cabin in 1976. One day, I got a phone call. It was Emmylou Harris, calling from L.A., calling me out of this farm. She said, What are you doing up there? She asked me to sing with her on her Elite Hotel album.

Two years ago, I took Grace back to see where she was born. When we pulled in, I caught sight of a neighbor behind a team of horses pulling a manure spreader. When he recognized me, he brightened. ‘Jon, get out of that car and spread some manure for me.’

As we talk, he and Sandy take us out to show us the garden, and this isn’t a haphazard garden. It is in perfect tune, in raised beds, with fall’s first monarch butterfly floating by: basil, cilantro, parsley, borage, lacinato kale, countless tomato plants, blackberries, and raspberries.

What’s musical about a garden?

The fertility. The order. The sense it makes to me, across the seasons, months.

There are ocean views everywhere in Cape Elizabeth. You didn’t choose one. Is there a hidden part of you, or do you carry your own shore with you?

We are very near the beach. We can ride our bikes there. I can listen here. I listen to the guy next door get up and go to work.

In your hit “Don’t Cry Blue,” you write, I’ve got to know the feel of every mile. How does this mile feel, out here in Cape Elizabeth, now that it’s been your home?

For five years. I’m feeling it really intimately and really well. When we leave, I tell my neighbors, Please, there’s no way I can pick these vegetables in the garden. Take anything you can, and they watch it for me. A few times a year some friends visit and we play outdoors. Anyone who wants to stops by.

Balancing global and local, do your neighbors think of you as the performer or the guy with the garden?

All of that.

What are your favorite haunts here?

We like to go to David’s in South Portland, and Local 188. I never saw the Bob Marley. But I love Maine’s Bob Marley.

Tell us about your first trip to Maine.

Our band, Headstone Circus [they also played under names like St. James Doorknob, and Finite Minds] had a gig at Loring Air Force Base, in way-the-hell northern Maine. At the NCOs club, not the officers club. I was wearing my vest with the stars from the American flag on it. We imagined going up on stage: Who were these hippies? It took forever to drive there the night before. Along the way, a crazy guy (I can say that because he would say it himself) in our band, Joe Dolce, acquired this rutabaga, the biggest I’ve ever seen. The night got darker and darker until we saw the giant runway lights wincing back and forth in white. (He waves his hands slowly.) Shhhh, shhhh. The lights were frightening, mind-splitting. Joe told us to pull over at the base of the lights, with the runway spilling out in front of us. He jumped out with his rutabaga. In our headlights he out walked toward the lights, holding the mystical rutabaga over his head. Poof. The lights went out, the sky went black. We looked at each other. Whoaaaaaa.

Okay, why did you really come here?

Maine: It doesn’t burn, shake, or fall into the sea.

0 Comments