Winterguide 2011

Interview by Colin W. Sargent

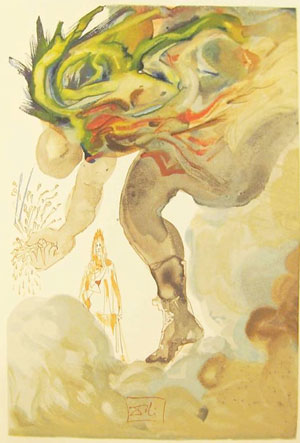

The White House, The Colbert Report…Holiday Inn By The Bay. Internationally famous poet Robert Pinsky’s March 7 pilgrimage to Henry Longfellow’s “beautiful town that is seated by the sea” in support of a Portland Museum of Art show creates an astral pairing of America’s first translator of Dante’s Inferno with his own, astonishing modern version.

Visiting this town as a poet without channeling Henry Longfellow is like slouching into Liverpool as a musician without The Beatles on your iPod.

Visiting this town as a poet without channeling Henry Longfellow is like slouching into Liverpool as a musician without The Beatles on your iPod.

There’s no way three-term U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky–here to promote the PMA show of Edward Weston’s 1941 photographs illustrating Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass–won’t have the bearded one (the first American to translate Dante’s Inferno in 1867) fixed on the ‘shoreless seas’ of his mind. He and Longfellow have shared a voluptuous intimacy in the dark woods of Dante Alighieri’s original Italian as fellow translators of the Inferno, enjoying the kind of rapport across the centuries lesser talents can only dream about.

When you went to Hell in 1995, was Longfellow there, waiting for you (or at least the residual sense of his highly-praised 1867 translation of the Inferno)?

Longfellow taught Italian literature, lectured on Dante. His gorgeous, blank verse translation was important to me. I used it as a crutch (or a trot, in the old expression) when I was making my version. His verbal music and scholarship were inspiring and useful.

Across the centuries, compare and contrast Longfellow’s translation with your own.

Longfellow’s sonorous, gorgeous lines are in Miltonic blank verse: the order of the words is, a lot of the time, the word order of Latin, rather than spoken English–which makes it an excellent trot, among other things, since he can maintain Italian word order (though sometimes difficult, especially after a while). Any 15 or 20 lines of it are rich and enchanting, but most American readers become exhausted by it, the pace and artificial idiom. Dante’s Italian moves very quickly. I try to use few words, and to convey that quickness and directness of the original.

To illustrate the flavors of three translations of Dante, please take us very close to your decisions about the line in the Inferno where Virgil answers the question about whether he’s man or shade.

Longfellow’s 1867 version: He answered me: “Not man; man once I was”

John Ciardi’s 1954 version: “Not man, though man I once was, and my blood”

Pinsky’s version: “No living man, though once I was,” he replied.

The Italian line is: Rispuosemi: “Non omo, omo già fui.”

Longellow gets an equivalent of that “omo, omo” repetition, enabled by the Latinate word order. I try to keep it simple and sayable. I guess the Ciardi is somewhere in-between?

Perhaps no living person can objectively assess Longfellow’s skills and reputation as you might. You even live in Cambridge! e.e. cummings snarked, “Christ and Longfellow, both dead…” Nostalgia aside, does Longfellow cut the mustard today? Or is he “pedastalled for oblivion”?

I’ve already said how highly I value his Commedia translation. I like some of his poems–e.g., “The Fire of Driftwood”–very much.

And there’s that wonderful video of Longfellow’s “A Psalm of Life” read by Rev. Michael Haynes at www.favoritepoem.org.

Tell us about your upcoming appearance and your admiration for Edward Weston’s attempt to capture Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in photographs he took across the country–including two in Maine–as part of the new show at Portland Museum of Art.

Whitman writes, “My voice goes after what my eyes cannot reach,” and in the same sentence “Speech is the twin of my vision.” Twins are not the same, even if some are called “identical.” So Weston’s photographs don’t so much capture Whitman’s poem as look in the same direction. Less illustrations than companions.

How do you rate the following famous poets connected with Maine: Edna St. Vincent Millay, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Robert Lowell*?

Robinson’s “Eros Turannos” is one of my favorite poems. As someone who comes from a small, seashore town (Long Branch, New Jersey) I think of it as one of the greatest American works about a town. It is in a way spoken by a town. (You can hear me read the poem at: youtube.com/watch?v=d7qTiKbI_eQ and there’s a wonderful letter about it in Americans’ Favorite Poems.)

Tell us a story about the first time you ever visited Maine.

When my kids were small, we went all the way up to Rangeley Lake: thrillingly remote, and beautiful. And for several years we rented a beautiful place on Lake Kezar, where the kids swam and fished, etc. But most memorably, we took the ferry (a four-passenger motor launch as I recall) to Cushing Island, for a rented-house vacation in that kind of insular community. I remember being on the beach and seeing big tankers pass close by. Our first night there–feeling like outsiders–there was a thunderstorm, and as the power went out and the house went black, we smelled smoke.

We called 9-1-1, I guess, and the fireboat came out from Portland. Turned out the lightning had hit the chimney, and what we smelled was long-accumulated soot. This adventure gave us an identity within the island community: We were the family in the house hit by lightning, and people were willing to chat with us about it.

Maine people can certainly connect with the emotional precision of your poem “Shirt” because we take great pride in the “earthly competence” of our creating, say, the L.L. Bean boot or the 1937 America’s Cup-winning J-Sloop Ranger. How do you define the Maine mystique?

The tradition of knowing how to do things, and knowing how things are made or repaired: I grew up somewhat familiar with that tradition, even on the Jersey Shore. In your, um, more austere climate, practical savvy is that much more important, I guess.

Hmm…“On Time And Under Budget.” Not exactly a poetry slogan, is it? Easier to imagine appearing in a poem by Whitman than one by Longfellow. Robinson might use it, saturated with irony.

There’s a delicate jazz to your poems in Gulf Music. How do you feel about the hoots and shouts of a poetry slam?

Performance can be a great art, but I am most interested by poetry in the reader’s voice. That is demonstrated by the videos at: www.favoritepoem.org. I’ve already mentioned Longfellow read by Rev. Haynes. Look also at the construction worker reading Whitman, the glassblower reading O’Hara, the Jamaican immigrant reading Plath.

What’s the best poem written to date that mentions Maine?

First one that comes to my mind is “Eros Turannos.” Whitman in his poem on election day uses the phrase “Texas to Maine.” If I was seeking, I’d look through Heather McHugh’s poems as well as Longfellow’s. And wasn’t Louise Bogan born in Maine?

Have you ever written a poem that takes place here? Could you please provide it for us?

Well, “takes place” may be an exaggeration…but here’s “Vessel,” which I remember writing on that vacation on Cushing Island. The childhood game of stretching out in bed at night and imagining my body as a boat sailing into sleep: Maybe the big ships on their way near the beach got mixed up with that?

Tell us about the moment when you decided, what the hell, why not translate the Inferno? So many scholars intentionally choose a small canvas for their work. How’d you shake off the ‘anxiety of influence’?

Not an issue at all–maybe I’m too insensitive to feel such a thing? I got hooked on the technical challenge, felt I had a way to make the poem quick and plain in English, and a way to create an equivalent of terza rima, without sacrificing idiom. It was more like having an absorbing new video game or sewing pattern or boat-building pattern than a large undertaking. It was like trying to master a song, or working on your jump shot or something. It was not consciously a scholarly or even a literary process: more athletic or musical or puzzle solving: working on a wonderful jigsaw puzzle or Sudoku.

If you could buy a place on the Maine coast, where would it be and what would it look like?

In a city or town, not isolated. More like Heather McHugh in Eastport than a luxurious compound. I like towns, I like streets. That hip neighborhood of Portland, maybe?

Do you enjoy lobster? How would it be served in the Inferno?

Yes, very much. Boiled.

What current Maine poets are on the map these days?

Not the kind of thing I tend to know, so I might omit someone obviously important. Among people I know, Heather McHugh lived in Maine for years, and I believe Annie Finch and Ira Sadoff live in Maine. But really, I don’t know–Americans in general, and writers in particular, move around so much that sometimes it’s hard to be sure who is where: something I feel double about. My family has been in Long Branch for three or four generations, and the place interests me endlessly–but I don’t live there! And my instincts are probably more cosmopolitan than regional, though I feel both those conflicting tendencies. On a less extreme wavelength than the Charbonneau of your novel, many of us tend to be hybrids that pop up in unlikely places.

Corresponding with a translator of Dante brought back a visit John Ciardi made to Lincoln Middle School in the early 1970s, where he did a presentation on poetry in our auditorium–mostly enlarging on concepts from How Does A Poem Mean. There was a lull toward the end…the sense of waiting for the bell. Then, to finish the show, he had his son come on stage to join a set of drums, and he played “Wipeout.”

Are you trying to get me to promise I won’t do that?

Who: Three-term U.S. Poet

Laureate Robert Pinsky

WHAT: 2011 Bernard A. Osher Lecture: “An Evening with Robert Pinsky: Is Vision the Twin of Speech?”

WHERE: Holiday Inn By the Bay,

88 Spring Street, $15

WHEN: Monday, March 7, 6-8 p.m.

INSIDE TIP: The release date of Pinsky’s highly anticipated Selected Poems (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, $26) is April 12. His “savage, inventive” Gulf Music, 2007, interpolates “voodoo music” with “special forces.”

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks