The film Ali, starring Will Smith, takes The Champ and his best friend, executive producer Howard Bingham, back to the days of the controversial Ali-Liston fight in Lewiston, Maine, in May, 1965.

Interview by Colin Sargent.

Muhammad Ali remembers Maine

Portland Magazine: What was the strangest thing about your fight in Maine?

Muhammad Ali: I don’t remember anything strange. I do remember going back to my room after the fight and having a bowl of the best ice cream!

PM: What one image comes back to you from that fight 27 years ago?

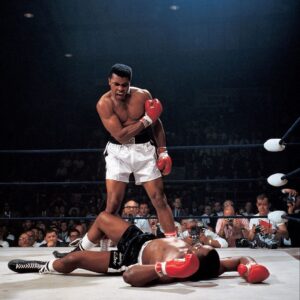

Ali: Sonny going down in the first minute of the fight.

PM: Did you get to try any Maine lobster?

Ali: Because of my religious belief I did not eat lobster.

They didn’t go to Steckino’s. They didn’t get any Maine lobster. But Howard Bingham had a fleeting thought: “They make shoes here,” he mused as his Muhammad Ali bus rolled past the Bates Mills in Lewiston, Maine, in 1965. “Maybe I’ll get some shoes.”

The bus pulled into the Lewiston Holiday Inn, and out popped Drew “Bundini” Brown, trainer Angelo Dundee, Bingham the legendary photographer, a black-suited retinue from the Nation of Islam; bizarrely, the politically incorrect comic Stepin Fetchit; and tall, graceful Ali.

“The Lewiston crowd would cheer us the following night,” says Bingham, “but we were still reeling because Malcom X had just been assassinated, and we’d traveled in under the cloud of that.”

It seems impossible for tiny Lewiston to have been chosen, but this was before the Las Vegas and Caesar’s Palace era. Ali had beaten Liston in Miami Beach on February 25, 1964, and the rematch had been scheduled for Boston Garden. On the eve of the Boston fight, Ali suffered a hernia injury, rendering the Garden booking no longer available.

“Our training camp for Boston was in Chickopee, Massachusetts,” says Bingham, and “something happened” to set the wheels in motion for Lewiston. “Ali had been in a lot of out-of-the-way” places before. Lewiston wasn’t out of the way, just a little further.”

So the fight was set for Tuesday, May 25, 1965, 10:30 p.m., at St. Dominic’s Arena, the Maine Youth Center, in Lewiston, Maine. Tickets sold for $50 and up. Harper’s Bazaar Gloria Guinness, Truman Capote, and Norman Mailer were at ringside for the Miami fight. Who would be here? Possibly the biggest break ever for ‘the cities of the Androscoggin.’

Once in the Holiday Inn, the champ tried to focus on the fight the next day. “Neither Ali nor I had been to Maine before, but there was no time for touring,” says Bingham. “He was focused on the fight, but imagine someone you loved [who had personally converted Ali to Islam] being murdered. It had been only three months…” A strangeness settled in. “We went around the hotel there. He had a lot of friends around and stuff, talking about the fight. Sonny Liston was billed to be a big, bad brute. They say he had ties to the Mafia. Other than that, outside the media, he and Ali got along. Ali and I visited him at his house in 1962 when he was out in Denver.”

In fact, Ali and Liston were a good deal more connected than the boxing public knew. Author Nick Tosches, in his dangerous new The Devil & Sonny Liston (Little, Brown, $24.95), figures that Liston owned about 10 percent of himself going into the fight. The ex-con, a fearsome puncher, had even purchased in a 1963 contract (as a partner in Inter-Continental Promotions) “for $50,000 the rights to promote Clay’s next fight after the 1964 Liston match [which Ali won in 6 rounds]. This was a staggering amount of money to pay for the future rights to a single bout by a fighter who was seen as facing almost certain destruction [Liston was heavily favored over Ali the first time around and an 8-to-5 favorite the second time aound] …”

When this got out, “[Inter-Continental’s] Jack Nilon, trying to explain the suspect pre-fight contract, said that ‘Clay represented a tremendous show-business property,'” but it led to a full-scale investigation by the IRS, who on March 3, 1964, “filed liens totaling $2.7 million against Sonny: $876,800 against him and his wife] Geraldine; $1,050,500 against Inter-Continental Promotions, Inc.; and $793,000 against Delaware Advertising and Management Agency, Inc., a Nilon-run sister corporation of Inter-Continental.” So we actually have Sonny Liston, d.b.a. the not necessarily reputable Inter-Continental Promotions, Inc., in concert with Lewiston promotor Sam Michael, to thank for this highly irregular Lewiston bout, trailed by real and imagined demons from the Mafia to the Nation of Islam (whom Liston feared) and the IRS.

Marooned here in Lewiston, the ill-starred Liston (in reportedly exquisite shape for the Boston date but edgeless in Maine) was simply not the people’s choice. He hadn’t learned to write his name until age 28. He had 23 brothers and sisters. He was from the wrong side of the wrong side of the tracks. He was later found dead at age 38, with a hypodermic needle planted beside him even though the boxer was so infamously afraid of needles he even refused novocaine from his dentist, according to Tosches.

“The fight was moved from Boston to Maine; Wherever the Bear goes he’ll end up in pain. Maine is known as the state of the Bear and the pine: When I got to Maine, I could not raid his camp, For I did not know which Bear was the ex-champ. The fight started without delay and in the fight I heard the Bear say… Please don’t beat me so bad, This is the worst whipping I ever had.”

-Ali to the media on the eve of the Lewiston fight.

On the fight night, Bingham was ringside as usual. There was a big jostle, bright lights. Ali started to dance. The Maine crowd, delirious with their momentary celebrity and oblivious to the Malcom X mourners, cheered like crazy. But in the time it takes to open a bag of potato chips, it was over and Lewiston was back in Palookaville.

“I saw the punch that put him down,” says Bingham, “but I’m not known as a fight photographer. I’m his friend. When he got hit, I got hit. I’ll have known him 40 years next month. I shot most of the fights, but my fight pictures aren’t that good because it’s hard to concentrate. I was new in photography. I just shot in available light.”

But the image endures.

There was Ali, standing over Liston, standing through the decades, shouting, “Get up and fight!”

Did Ali feel cheated that Liston’s going down so fast might make it a controversial fight?

“No,” says Bingham, “people’s different opinions about things make the world go round. Naturally there was controversy about his being hit or not hit, but when they replayed the frames, you could see the contact, and Sonny’s head moving, and the sweat spraying off his head.” Even when they called it a phantom punch “it didn’t annoy him. Nothing annoys him. They were fighting at close quarters, and this was a short right. I remember he once explained to people that when ‘a couple of diesel engines come together and contact, there’s going to be a boom.'”

“There was a short right hand that connected. But Liston was scared, he was connected to the mob, he was even nervous about the Malcom X people at the fight,” says Pete Morkovin, of Pennsylvania and Florida, now a world-renowned collector and seller of memorabilia from the fight. Years ago, as a water boy in Ali’s training camp, he tiptoed up to Ali and asked him about the Lewiston fight directly. “I used to go to Ali’s training camp. He bought a small training site in Deer Lake, PA, from 1972 to 1980. I used to go up there every day to watch, run errands for him, get his mail, run and grab a sandwich – he was incredibly generous, often sending me out with $50 bills and telling me to keep the change. Well, I asked him one time in his cabin about Lewiston. He thinks Liston didn’t want to fight that day because he might have been out of shape, or just tired, because of the missed fight day.

He was fed up with everything, frustrated by the Mafia, thrown by the entourage Ali was with. He was in such good shape for the second fight, and having that fight rescheduled-he just wasn’t there. Ali might have stunned him with that punch, but he was accustomed to taking much rougher treatment. I just think he didn’t want to get up and go through the rest of the fight. Who would want to? No one had ever seen anybody as fast as Ali.”

Did Ali ever complain to Bingham about how short the fight was?

“No, I think he wished it could have been faster. A guy wants to win and win convincingly, and deep down within I would think someone would want to win right away. That night it happened in a minute or so, and it was a relief not to be punished by all those long rounds where you could get hurt and cut. I’m sure he was happy and excited it was over. Think about it. If you were going to make a lot of money, and had a hard fight to hold, would you want to get it over with quickly?”

“Besides,” says Morkovin, “Liston’s trainer after the Miami fight admitted to putting linament on Sonny’s gloves to blind Ali. It must have been excruciatingly painful.” So Ali wouldn’t have wanted to wait around for that to happen again.

According to Tosches in The Devil and Sonny Liston, “the winner of a good fixed fight never knows that he is a party to the fix. It has been said that it is harder to throw a good fight than to fight one. But human vanity on the part of a victor does much to compensate in his heart and mind for any suspicion of inauthenticity on the part of his foredoomed opponent. The performance in Lewiston, however, was so bad that even Ali must have known.”

After the fight, “Sonny Liston’s name came up,” says Howard Bingham. “Oh, sure. We saw Sonny Liston now and then.”

On March 29, 1966, Sonny bought Kirk Kerkorian’s place in Vegas for 64 grand: split level, pastel green, with a swimming pool and a backyard that looked out over the sixteenth fairway at the Stardust Country Club. The address was 2058 Ottawa Drive, in the exclusive area of Paradise Township, less than a mile from where his hero and buddy, Joe Louis, lived, at 3333 Seminole Circle, in a house bought from Johnny Carson,” writes Tosches.

A reward? A straightforward transaction?

Strange connection – billionaire Vegas hotelier Kirk Kerkorian is in the news today as his wife’s attorneys negotiate a child-support settlement of $300,000 a month, the highest ever, for his two-and-one-half-year-old daughter.

Did Ali help Liston financially after he got deeper into drink or drugs (though he continued his active fight career until the end of his life)?

“No,” says Bingham, though Ali followed his career with near fascination. “In fact, we went to his funeral, in Las Vegas. There were people there. And then, at the end, Ali walked over to Sonny’s widow and talked with her. He leaned over and whispered something into her ear.”

Do you know what he said?

“What?”

What Ali said to Liston’s widow.

“No.”

Something about the lady and the tiger. Somebody ought to send these guys a good pair of shoes.

0 Comments