By Lewis Turco

Peter Ross Perkins and I met in 1953 in New York City after I was transferred from Bainbridge, MD, to serve aboard the U.S.S. Hornet (CVA12), the eighth ship to bear that name. As the CV12, she had been launched 10 months after the seventh Hornet had been sunk in World War II, but she, too, had seen much action in the War. Now, she had been recalled from retirement to be redesigned and refitted in what the Bureau of Naval Personnel called “The Oriskany Conversion,” to serve during and after the Korean War. She was to be launched in all her renewed glory from the Brooklyn Naval Shipyard.

Peter Ross Perkins and I met in 1953 in New York City after I was transferred from Bainbridge, MD, to serve aboard the U.S.S. Hornet (CVA12), the eighth ship to bear that name. As the CV12, she had been launched 10 months after the seventh Hornet had been sunk in World War II, but she, too, had seen much action in the War. Now, she had been recalled from retirement to be redesigned and refitted in what the Bureau of Naval Personnel called “The Oriskany Conversion,” to serve during and after the Korean War. She was to be launched in all her renewed glory from the Brooklyn Naval Shipyard.

Peter, who was three years older and a native Mainer, had attended Deering High School in Portland where he played for three years in the school band with, among others, his friend Priscilla Riley–later Priscilla Smith, wife of David Smith, Dean of Hampshire College in Massachusetts. Priscilla describes their acquaintance thus:

I knew Peter well through our association for three years in the excellent Deering High School Band. Peter was our tympanist and I was one of the four baritone players. He was a year ahead of me in school and a very bright student. One of the things I most admired about him was his proficiency, even as a high school student, in French. I remember him walking me home one night from an event where I tried to talk French with him, and realized how naturally it came to him and what a struggle it was for me. I believe I last saw him at a summer Kotzschmar organ recital at City Hall, but that was ages ago.

I had been born in Buffalo, New York, but brought up in Meriden, Connecticut, where my immigrant father was minister of the First Italian Baptist Church. I had joined the Navy directly out of Meriden High School in 1952. After Peter graduated from Deering High he had attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, but after three years he had dropped out and joined the Service the same year I did.

I was one of the yeoman clerks in the Gunnery Division office of the Hornet. Peter was a member of the Division as well, but a Fire Control specialist (“fire” as in “ready, aim”). I don’t recall the particular day we got to know one another, but we were fast friends before the ship was re-commissioned.

The Hornet was at last finished, and the crew moved aboard from temporary quarters ashore; eventually the ship was launched and we went on sea trials which were followed by a shakedown cruise to the Caribbean.

When we arrived at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba Peter was left out of an adventure I alone, out the the whole crew, experienced. I spent a day with one Rev. Withey, who came down to Guantanamo Naval Base on orders from my father! The base chaplain got me off the ship for an entire day at the end of January, 1954. I spent it with Dr. Withey, two other ministers who had come down with him, and with the chaplain.. I had, and still have, no idea how my dad managed to manage this feat. The preachers and I went into Havana, which no one else was allowed to do from the Hornet because Castro and Che Guevara were raising Hobbs in the hills.

In the morning, while I was waiting at the base library for the ministers to arrive (I had been dropped off before the ship sailed for fleet exercises) I read “The Song of Songs” and was transported: the scenery was much like the Middle East, I imagined. Afterward I lay down and stared at the fish swimming off the pier: a thousand brilliant colors. It was as though I were gazing into a gigantic, more brilliant version of the aquaria I used to maintain in the sun porch of the parsonage on Windsor Avenue in Meriden.

Then came the day we visited Haiti on the sixth of February, 1954. We steamed into the harbor between vast, eroded hills and verdurous shoreside farmlands. I spent the day on Shore Patrol duty with Peter in Port au Prince. Neither of us had ever done anything like this before, nor had any training for it, but our job was to wear SP armbands and wander around town checking into bars and other establishments frequented by sailors, to make sure that there were no untoward incidents taking place. Peter’s facility with French came in handy that day. We were lucky, though–nothing much happened. The marketplace seemed like a page out of a pirate story. We were offered articles made of mahogany, teakwood, and alligator skin.

Much of the city of Port au Prince had not changed a whole lot from the days of Henry Morgan, apparently. Much of it was squalid and unspeakably filthy. All of this merely emphasized the gulf between the truly modern portion of the town where the foreign population lived and did business: tall buildings of progressive architecture, exotic night-clubs and hotels, and spic-and-span living districts. Many American tourists were on hand to greet us. Peter and I spent another day wandering around Ciudad Trujillo on the other side of the island, in the Dominican Republic. It seemed to be a bit more civilized.

When our shakedown was done, we returned to Brooklyn to await the beginning of our showcase World Cruise. The U.S.S. Hornet sailed around the 13th of May from Newport News, Virginia. Lisbon, Portugal, was to be the first stop, then Naples, Italy. In Lisbon Peter and I and a couple of other sailors went out on the town and were sitting at a booth in a bar after a full day of sightseeing, talking — as best we could — with a little Portugese boy. We gave him some Navy memento or other. A young man at the bar with a couple of friends called him over and took it from him, looked it over. We thought he was trying to rip the boy off, so we began to mutter things like, “You take the skinny guy and I’ll get the fat one.” Then I glared at one of the young men. pointed at him, then at the boy, and said, “You, no! The boy, yes!” He replied in perfect English, “Yes, I understand, it belongs to the boy.” He spoke English better than we did.

So we struck up a conversation with the young men, and then we went out on the town together. They took us down narrow cobblestoned alleys where lovers were making out in ancient doorways. We went into severalfado houses, listened to fado songs, ate olives, and drank wine–the fado was the national music of Portugal, rather like our blues, but quite different rhythmically. It was a beautiful evening. We all swore to keep in touch with one another, exchanging addresses. Before we said goodnight and farewell we promised to write each other. Of course, we never did, though I tried once, if I recall correctly.

At the end of May we put into Naples harbor. While we were in port a train tour to Rome was arranged, and we saw the classic places: St. Peter’s Basilica, the Coliseum, the Forum, and we walked around town buying gifts for the folks back home–I bought a pipe carved in the shape of Romulus and Remus suckling the wolf; carved underneath it was the legend, “R-Roma.” It took me a while to get the pun.

Back in Naples Peter and I tried to walk to Mount Vesuvius, with small luck, for it never seemed to get closer. We finally managed to get to Pompeii by taking a train. Unfortunately, by the time we arrived the exhibits were closed, so we dropped into a trattoria and had a big spaghetti meal and about a half-gallon of chianti. By the time we got back to the ship we–especially I–were in rather rough shape.

When the cruise continued we passed Stromboli, Sicily, and Italy through the Straits of Messina, and pressed on through the Suez Canal. We saw the Pyramids in the distance, sand spreading to the horizon, and paused briefly at Port Said before sailing on to Colombo in what was then called Ceylon and now Sri Lanka. While we were making our way through the Red Sea Peter and I saw, while we were standing at the rail, an immense fish lying at the surface of the water beside our ship. It was a whale shark. It looked big even beside an aircraft carrier.

On a tour to Kandy, our bus stopped at a waterhole where a mahout was giving his charge a drink and letting it cool off by spraying water over its back. He offered us rides, but we were wearing whites, so Peter and I demurred, but some of the sailors accepted. The elephant reached out its trunk, grasped them in a coil, and put them up on its back for a brief ride. They continued the tour looking something like black-and-white barber poles.

The sun was hot and bright when the Hornet dropped anchor in Singapore Harbor. The city lay like a crescent off our port beam; myriad islands and ships flying many flags speckled the waters to the horizon.

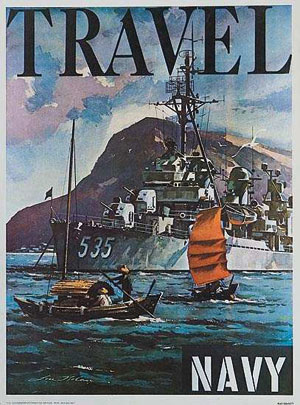

For many of us this was the first time we had seen junks. They were a strange sight as their weather-beaten hulls and mat sails wove in and out among Chinese freighters, Dutch liners, South American and island trading ships, and tankers from the United States making for the open sea or berths in the harbor.

Peter and I took the tour to Johore Bahru on the Malayan mainland and saw much of Singapore through the windows of a bus. We passed native market places and modern department stores, mosques in the traditional Arabian manner and a tremendous Church of England; blond and auburn-haired Englishwomen and swarthy Asiatic girls, all of whom looked perfect to the eyes of sailors who had been at sea for a while.

Johore Bahru is connected to the island of Singapore by a causeway. As we passed from Singapore into its sister city, we left the Occident and entered the Orient. The Sultan’s palace was huge and golden as we passed it on our way to the Sultan’s Mosque. Its grounds were extensive. Small elephants and chickens seemed to be the sole inhabitants of its gardens and woods.

When we left the mosque, our bus took us back through the gardens and roads that twisted through the outskirts of a zoo. Half the day was gone. Finally, back in Singapore, after we had eaten, we again sallied out into the streets and alleys of Singapore.

Night was falling. Around us the stone buildings and monuments took on the grey tinge of evening. In the harbor, lights were lit aboard the ships and varicolored flags were furled. The water became dusky, and the ripples stirred up the ever-moving junks; bumboats glinted in the sunlight reflected from the clouds. Silhouettes of ships became black, and then indistinct, fading at last into the darkness. Then we heard the bells of our liberty launch. Our day in Singapore was ended.

When the Hornet crossed the Equator everyone was given a subpoena. I don’t recall how Peter’s read, but “Charge 4” of the subpoena I was given to appear at the Court of Neptunus Rex was, “Scribbling poetic doggerel on Navy time.” All our hair was shaved off as part of the initiation, and the seadogs made us crawl through parachutes stuffed with offal. We were spanked with paddles as we ran a gauntlet, given a vile concoction to eat, et cetera, and we graduated from Pollywog status to that of Shellback.

We continued our voyage to the South Pacific and were in Subic Bay, the Philippines, for a day, then we operated around Corregidor and wound up in Manila Bay. One day as Peter and I were going ashore to Cavite City in a forty-foot motor launch, Peter shouted, “Look!” and pointed astern. I craned around and saw a waterspout heading across the harbor toward us. One of the boatswain’s mates aboard flung open the hood of the engine amidships, stuck his head in, and removed the governor. The launch was going so fast that it began planing, but the spout was gaining. Suddenly, it hit the protruding mast of one of the sunken World War II ships that were in the harbor, tore it off, and disappeared in a whiff. Peter and I and everyone else aboard breathed a great sigh of relief, and the coxswain slowed us down. We got ashore with no further incident.

By the 26th of July the fleet was searching the Indo-China Sea for the wreckage of a British airliner the Chinese had shot down on the 23rd. At General Quarters Peter was below-decks spinning his gun control dials, or whatever it was they did down there, and I was on the Gunnery Bridge standing watch at Gunnery Plot, a transparent plexiglass board behind which I stood with earphones on. I was in contact with CIC which gave me the coordinates of our airplanes and any “bogies.” Planes from our carrier and the Philippine Sea were suddenly jumped by two bogies. Our planes engaged, and over my phones I heard, “Scratch two bogies!” I peered around the edge of the board and asked LCDR Edwards, “What means scratch two bogies?’” He said, “They shot ’em down!” I was stunned.

The next day, the 27th of July, I was up on the gunnery bridge of the island again watching air ops when I experience a truly powerful feeling that one plane would crash, I watched a jet come in for a perfect landing, stop, fold its wings, and taxi toward the port side of the ship to be spotted forward on the flight deck. With great relief I turned to look at the next plane coming in. Suddenly, I heard a rending sound. I turned to look back at the first plane–its jets hadn’t cut out! They kept pushing it forward (afterwards I could see the skid-marks curving across the flight deck). I saw it teetering on the edge of the ship, its fore-gear momentarily resting on a radar housing. I saw the radar operator standing in the middle of the flight deck screaming into his headset microphone, but the wires to the headset were dangling, torn out of the panel in the radar shack he had suddenly abandoned. The plane tilted nose down, parallel to the side of the ship–I saw its tail sticking straight up–then it disappeared out of my range of vision.

Peter and I learned later what happened next: the plane hit the water nose-first, then fell over on its cockpit, trapping the pilot, and sank immediately. The pilot, LTJG Thomas Moir Gardiner, disappeared forever. Appalled, I resolved never to watch air ops again.

We resumed our regular duty, which was to patrol the Straits of Formosa–now Taiwan–while the Chinese were bombarding the islands of Quemoy and Matsu which were in Nationalist Chinese hands, like Taiwan, not a part of Communist China. The duty was routine, but for some reason we were never to visit Nationalist China itself. We had to make do with Japan where we went for repairs, maintenance, and R&R, and with Hong Kong, China.

Peter and I found that Japan’s seasons felt like those in the U. S., except that there was an edge to them, because there was something piquant about the scents of the air and the evergreens. Tokyo was an amazing place to visit, especially The Ginza, which was a lot more like America than much of America was. I found a set of little ivory carved birds for my fiancée, Jean Houdlette, back in Meriden. We weren’t in Yokosuka Harbor for long, however, only a couple of weeks.

But what a town Hong Kong was! The Hornet hauled into the harbor and dropped anchor. Mary Soo, “Garbage Mary,” was there with her girls to collect our offal before the anchor had time to get well-soaked. I suppose the garbage was used to feed pigs on Chinese farms. The sampans and bumboats were omnipresent. Maybe the water taxis were lopsided and couldn’t do more than a knot, but they got Peter and me and many another ashore, and they got us back aboard loaded like barges with “Real ‘No-Squeak’ Young” boots, Taj Mahal suits and trousers, bamboo furniture, little carved chests and what-all.

Ashore we jostled along through crowds of Chinese, Indians, British troops, American tourists; beleaguered and badgered by rickshaw boys and sidewalk vendors; awed by women in the slinky slit skirts. Hong Kong: King Kong of the Chinese coast. But it loomed even larger in our eyes for a simple reason: it was nearly our last stop. Before we got to Hawaii, though, we had to cross half the Pacific Ocean.

When we got there in December Waikiki Beach by night was a crescent of white sand ending at Diamond Head. The Royal Hawaiian Hotel was the main feature of the beach, set among its palms. We saw the sunken battleships at Pearl Harbor and took part in a ceremony honoring those killed in the Japanese sneak attack of December 7th, 1941–it was an anomaly to recall how we and our old enemies (not so old, at that) were getting along at the moment.

A couple of decades later I would visit Hawaii again, as a representative of the faculty of the State University of New York at Oswego, and Waikiki would be all but unrecognizable. The pink Royal Palms was still there, but it was insignificant among the wall of skyscraper hotels that surrounded it and blocked the beach off from the public beyond, and Diamond Head was still plainly visible, but now it looked down upon rooftops, not sand.

On our way across the rest of the Pacific we ran into an immense typhoon. I don’t know about Peter, but I got seasick only twice in my Navy career–once was while we were on sea trials, and the next while we were riding out this monster blow. The storm was the most incredible sight. When General Quarters sounded I went racing up the tower to my station at Gunnery Control, and as I did so the escalator stairs beneath my feet fell away and I was floating in mid-air. I kept my balance somehow and came out on the Gunnery Bridge to see the great ship poised on the lip of a simply gargantuan wave, heading down.

We dived like a porpoise, and when we hit the trough we started up the hill again, but not before the wave crested and broke…halfway along the flight deck! I had seen this happen in gales to destroyers and destroyer escorts which, it seemed to me, were more than half submarines, but I’d never thought to see it happening to an aircraft carrier. Somehow, we rode out the storm, but our hangar-deck doors were a wreck by the time we hit port in Oakland, California.

At that point Peter and I decided to build a large hi-fidelity set in the ship’s carpentry shop. We asked and received permission to do so, and several of us went ashore to a lumber yard to buy what we needed. When we returned to the Hornet we ascended the gangway and approached the Officer-of-the-Deck with a 4×8-foot rectangle of plywood balanced on our heads. All four of our sailor caps were placed directly over our heads on the plywood, and we saluted with our right hands to its edge as we asked permission to come aboard.

The hi-fi set was, indeed, built, and not long afterward, while our ship was in San Diego, I received orders to be transferred to the Bureau of Naval Personnel in Arlington, VA, where I would spend my last year of service working on the Navy’s Shore Duty List, a fabled position in the fleet. I had the set shipped home, and then I followed it, but not before I had introduced Peter and some of my other shipmates to one of my cousins, Josephine Sardella, a former Navy nurse, who lived in San Diego. A bunch of us went to her apartment and had a fine Italian meal of spaghetti and meatballs, the first one Peter and I had had since the one in Pompeii.

The week before I was to be shipped cross-country Peter and I were up on the hangar deck of the Hornet. I was listening to him practice pieces on the ship’s organ which he played for Sunday services. I had sung all my life, so I began to sing along with him as he played “A Mighty Fortress.” Peter said, “Let’s try it up here,” and he pitched it quite a bit higher. I have a big voice, so I began to belt out the hymn. We had attracted a small audience. When we were finished the Chaplain stepped forward to approach me. “Would you be willing to sing at services this coming Sunday?” I begged off. “I’m being transferred this week,” I said. We were both disappointed, but Peter would make it up to me later on.

While I worked my last year in the DC area, Peter remained aboard the Hornet. They traveled up the coast to Bremerton, Washington, and had a canted flight deck installed. I lost touch with him for a while.

On June 16th, 1956, a week or so before I was discharged, Jean and I were married by my father at 2 p.m. in her church, the First Congregational of Meriden. All our high school friends were there and my brother Gene was Best Man.

My new in-laws were native Mainers who still had family property in Dresden Mills. My father-in-law, John Houdlette, had been my 7th-grade shop teacher at Lincoln Junior High School where I remembered seeing Jean on the first day of classes in 1947. She was my classmate at Meriden High also, though we didn’t begin to date until I’d joined the Navy.

Jean had just graduated from the University of Connecticut in the spring of 1956. I returned to DC mainly to be separated from the service. When I returned to Meriden I built houses with my father-in-law during the summer before I myself entered UConn as a sophomore: I had taken courses and tests from the Navy and USAFI to earn a year’s college credits. I had also spent most of a yeoman’s idle time at sea reading books from the ship’s library, teaching myself how to write professionally, and beginning to publish in the literary magazines of the period. By the time I got to college I had published more than some of my teachers, which caused a problem or two

After our wedding reception Jean and I drove to the Cate Farm (Jean’s middle name is Cate) in Dresden Mills where we spent our brief honeymoon and where I did little except sneeze because I was allergic to the kapok mattresses in the house, which was quite primitive in other ways as well, including the water supply.

Peter returned to Portland and, in the fall, to Brunswick to finish his BA at Bowdoin. In 1966 he received an MA in French from Middlebury College where he was organist and carillonneur as a graduate student. Later he taught French for more than a decade at several New England schools, but he always maintained his interest in the organ.

Peter hadn’t attended our wedding–I don’t remember why not–but we saw him in Maine. Jean and I decided that Peter ought to meet our dear friend and classmate Marie. We loved them both and thought that they’d make a great couple. We arranged for them to get together and…disaster! Neither my wife nor I had ever witnessed two people who so detested one-another on sight. We spent an agonizing evening together and never tried anything like that again.

I graduated from UConn in mid-year 1959 and was a teaching assistant there for the spring semester before transferring to the Writers’ Workshop of the University of Iowa as a Fellow in poetry and Editorial Assistant to the Director, Paul Engle, in the fall. I was at Iowa for only a year because my wife became pregnant and I needed to get a job to support her and my imminent daughter, so I left without taking a degree.

My First Poems, however, was published in the summer of 1960 as a selection of The Book Club for Poetry by Golden Quill Press. By sheer coincidence I was offered my first academic position at Fenn College in Cleveland where one of the editors who had chosen my book, Loring Williams, lived and had a press.

I had met Loring at a writers’ conference while I was an undergraduate. Loring was a native of South Berwick, and he was one of the founders of the State of Maine Writers’ Conference at Ocean Park, so he invited me there the summer my book came out to give a program and meet the other two editors, George Abbe and Clarence Farrar.

When I arrived in Ocean Park, I discovered that I was not unfamiliar with it, because it was not only the site of the Conference, but it was also the place where I had attended the Baptist-affiliated Royal Ambassadors Boys’ Camp for two years as a child…my father had been a leathercraft instructor there! From that point on Loring and I were in collaboration on many a project, including the Cleveland Poetry Center which I founded in 1962.

Of course, as a college instructor (I finished my Iowa degree in 1962) I had my summers free, and my family spent most of them from then on in Dresden Mills. I not only renewed my friendship with Peter Perkins, but we saw a lot of each other. It was during this period that Peter–who was the organist of a church in Brunswick, I think it was, or perhaps Falmouth–decided we would recreate the scene aboard the Hornet when the Chaplain had asked me to sing “A Mighty Fortress.” Peter invited me to come sing at his church on a Sunday, and I agreed.

Unfortunately, those kapok mattresses were still in the old farmhouse. When Jean and I got to Brunswick I asked Peter not to pitch the hymn high this time, but he forgot…or something. There was no way in the world I was going to hit those high notes he began playing, but I tried. It was the most dreadful solo anyone anywhere has ever heard. Nevertheless, afterward an old woman came up to me and told me how much she had enjoyed it. I confess I wanted to kill her, and Peter, too.

I got a small measure of revenge that summer when I went up in the attic, opened the window, and threw all the kapok and feather mattresses stored there out into the dooryard. It was a blizzard of feathers and stuff. The lawn was covered with what looked like snow that would never melt. I don’t remember how it was done, but somebody cleared up the mess and I sneezed no longer.

Besides the State of Maine Conference I began doing summer programs here and there in the neighborhood. One of these was the Damariscotta Lake Seminars that had been founded by Al McLain and his collaborator David Smith, Priscilla Riley Smith’s husband. They asked me to be a member of the summer faculty there, and I was happy to accept and get to know the McLains and Smiths. “The nice part for all of the faculty,” Priscilla recalls, “was that the families stayed there and were always welcome at lectures and classes. I have memories of Jean McLain and some of the others with our children at the Biscay Beach, especially Ann (and Dave) Gruender from Ohio, and Ursula (and Gerhardt) Probst of Kentucky. There you have most of my memories, except your reading poems, especially, ‘Chorale of the Clock.’”

There is a Maine connection for the poem Priscilla remembers. Loring Williams was married to one of the aunts of Hart Crane, Alice Crane Williams. I used to go over to their home at least once a week as long as I lived in Cleveland, and on many of those occasions Loring and I would sit and listen to Alice tell stories about Hart, her other relatives, and her adventures as the composer of various musical pieces. One evening she mentioned a strange disease I had never heard of, “tic douloureux.” I couldn’t get it out of my head, so I had to exorcise it by writing the poem Priscilla recalls,

CHORALE OF THE CLOCK

(“Tic douloureux,” pronounced tik doo-loo-roo or tik da-ler-oo in standard and colloquial English respectively, is a very painfully diseased nerve.)

There was a woman on our block

(Tick, tock, the town cock crew)

And every dusk she wound the clock

With a large brass key she hid in a sock

Under the rug by the panel door.

Then she’d rinse her cup and sweep the floor,

Let out a sigh, the gray cat too —

Tock, tic douloureux.

And when the cat was gone, she’d lock

(Tick, tock, the town cock crew)

The doors, the windows, the cookie crock,

The casement of the grandfather clock.

Then she’d hide her key and go up to bed

To dream in the feathers of her bedstead,

Dark where the canopy nightbird flew —

Tock, tic douloureux.

Still, in her sleep she would mark the clock.

(Tick, tock, the town cock crew)

Every chime was a mortal shock:

A nerve in her cheek would jerk and knock;

Something or someone would begin to scream

As pain spread slowly across her dream,

And she’d start awake with the devil’s ague–

Tock, tic douloureux.

All night long she would lie and rock

(Tick, tock, the town cock crew)

In a boat of shadows at Charon’s dock

Hearing the shades on the far side mock,

Jeering and asking her why she stayed

So long away. “I am afraid,”

She said, “of the darkness and of you….”

Tock, tic douloureux.

“I fear the warden of my clock

(Tick, tock, the town cock crew)

May some night forget to test its lock;

The convict, discard her prison smock;

The emptiness of the time I serve

Burst the manacle of this nerve,

And the walls of my being prove untrue.”

Tock, tic douloureux.

She sighed as she saw the nightbird rise;

The nerve quit jumping. She closed her eyes,

And then she lay quiet, still as the dew.

Tick. Tock. The town cock crew.

As the years passed Peter took first one position and then another, and at one point he opened a home decorations business in, as I recall, Yarmouth, which Jean and I visited one day. His former wife Margaret continues to live in Yarmouth.

In the spring of 1969 Jean and I went to Bernardston, Massachusetts, to visit Peter and Margaret, who was to have a baby in the fall. When we heard nothing, and then when we got their Christmas card with no child’s name, we suspected something had gone wrong.

Not long afterward I stayed up all night reading The Golden Bough, went to bed around 7 a.m., and dreamt I was visiting Peter and Margaret alone. I was afraid to ask them about their baby. Then I heard a cry in the next room and Margaret excused herself to go take care of the child. I thought in my dream that Jean would be relieved to hear everything was all right.

I woke around noon. At 2 p.m. the mail came. In it there was an announcement of the birth of Christina Beth Perkins on Feb. 17th.

Peter and Margaret had two children, a daughter, Christina, and a son, Douglas. Jean and I also had a daughter, Melora Ann, and a son, Christopher Cameron, but the two families never got together as a group. Peter dropped out of sight over the years, and not many moons ago Priscilla and I talked about him and we tried to find him, but I couldn’t get him by phone, and we began to assume the worst. Then I had a major operation in 2013 and David Smith died, so we both stopped searching.

At last, Priscilla wrote me the second week of January, 2015. “Although I could not make the picture in today’s paper look like Peter, I know it is he and I am saddened that I was never able to be in touch with him. I was also surprised that he was at Village Crossings in the Cape, where I regularly visit my sister-in-law. I expect you will be inspired to remember him in verse. May he rest in peace with lots of beautiful organ music. Priscilla.”

0 Comments